2018 Clinical & Dermatopathologic Cases

1. Peripheral T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, NOS CD4-/CD8-/BF-1+

2. Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm- An Underrecognoized but Deadly tumor

3A. A Unique Case of Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma Mimicking Mycosis Fungoides

4A. Congenital Leukemia Cutis as Presenting Feature of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

4B. Leukemic Infiltrate Secondary to Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

5B. Pigmented Spindle Cell (Reed’s) Nevus with Chromosomal Mutations

6. A Case of Desmoplastic Malignant Melanoma: A Diagnostic Pitfall

7. Ectopic Extramammary Paget’s Disease Presenting on the Face - An Extraordinary Case

10. Basal Cell Carcinomas Appearing During Immunotherapy for Reported Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma

11. Cutaneous Metastatic Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma and Hand-Foot Syndrome

15A. Stewart-Treves Syndrome at site of Cavernous Lymphangioma

15B. Unusual Pigmented Angiosarcoma With Epithelioid Features Simulating Melanoma

16. Glomangiosarcoma

17. Cutaneous Endometriosis of the Umbilicus (Villar’s Nodule)

18. Tattoo reaction with pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia to red pigment

20. Migrating Filler

21B. Bullous Morphea

24. Psoriasiform Dermatitis Secondary to Pembrolizumab Therapy

29A. Atypical (persistent) Eruption of Adult-onset Still’s Disease

29B. Adult Onset Still’s Disease with Macrophage Activation Syndrome

30. Symmetrical Drug Related Intertriginous And Flexural Exanthema (SDRIFE)

32. Nocardiosis

33. Dysmorphic Trichophyton rubrum Infection Simulating Blastomycosis

Case 1: Peripheral T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, NOS CD4-/CD8-/BF-1+

Caregivers: Patrick Henry McDonough, MD, Etan Marks, DO, Clay J. Cockerell MD; Dallas, TX.

History: A 56 year old woman presented with a 4 month history of ulcerated plaques and nodules of the trunk and extremities. She complained of no “B” symptoms. She had a past medical history of fibromyalgia, depression, asthma, and hypertension. She is currently on Buspirone, Gabapentin, Losartan, Pantoprazole, and Venlafaxine.

Physical Examination: Scattered red papules and plaques with focal areas of necrosis and ulceration on the back of the neck, mid-back and legs.

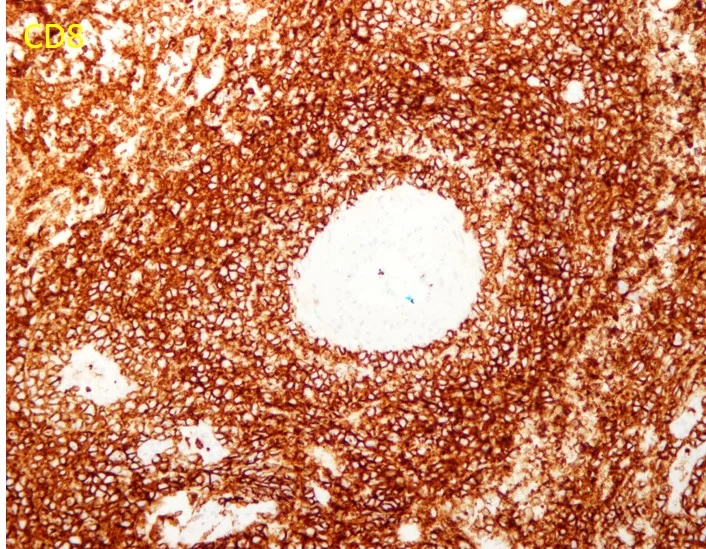

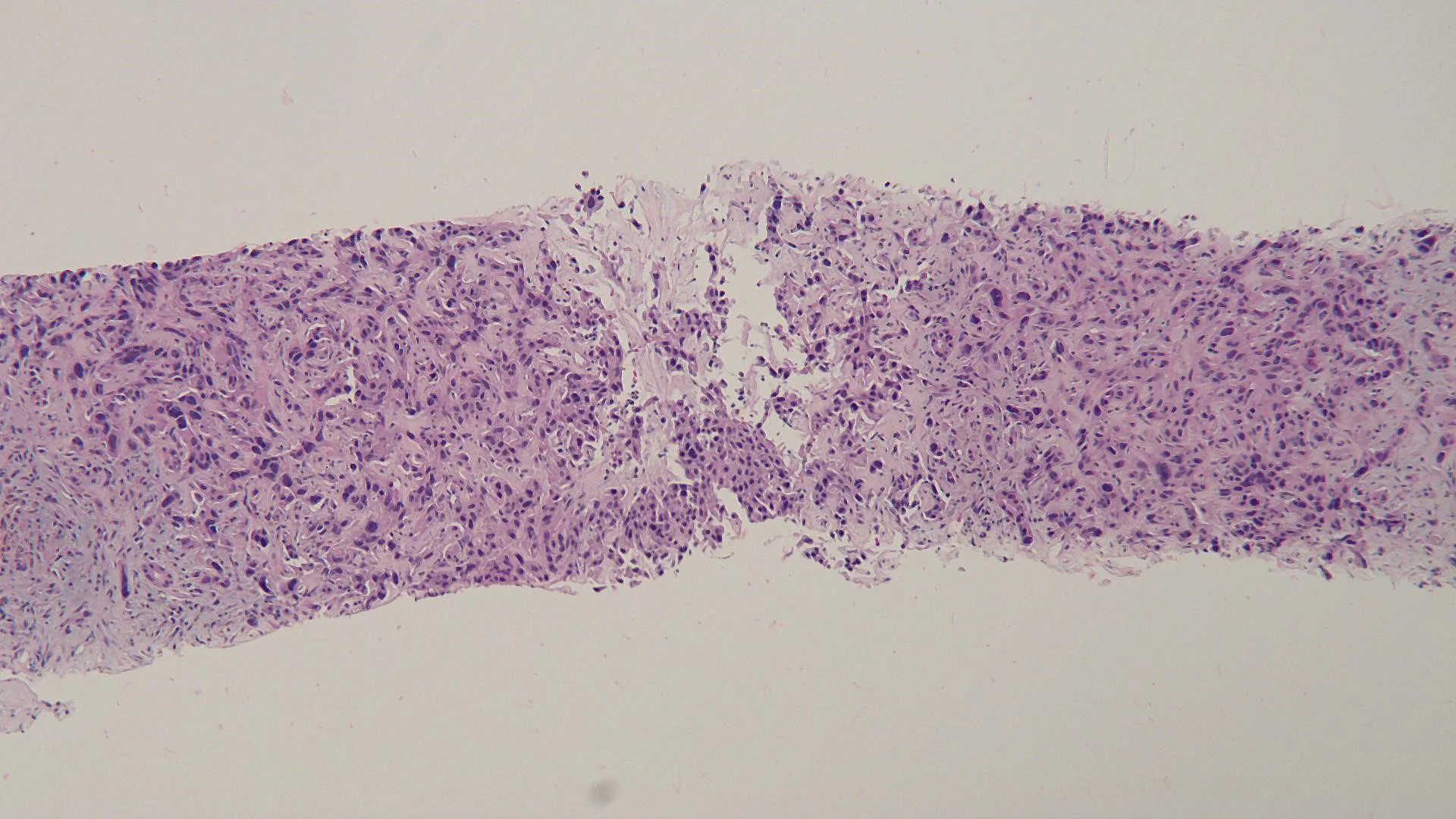

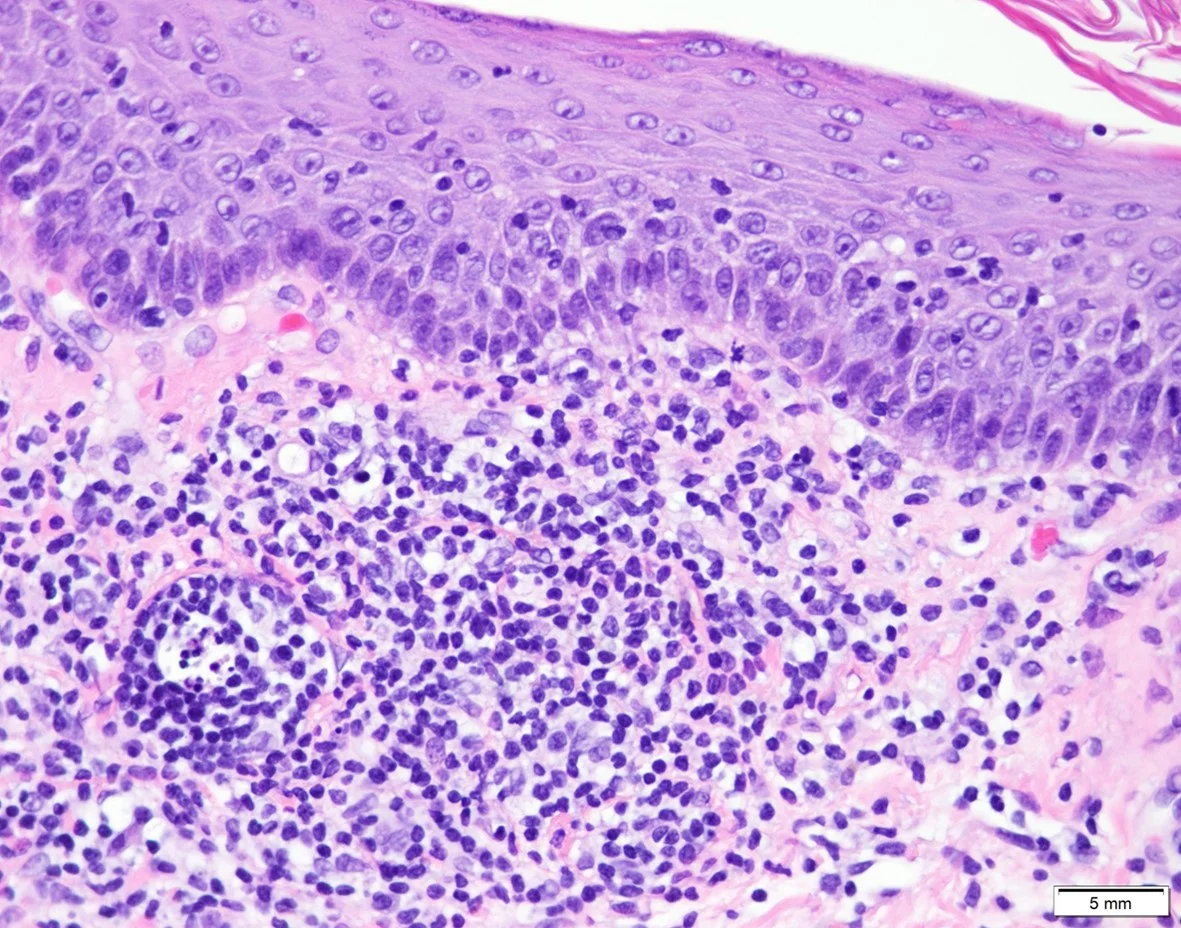

Histopathology: Band-like papillary dermal lymphoid infiltrate with epidermotropism comprised of large lymphocytes with irregular nuclei. The cells stained positively for CD3 and Beta-F1, but were mostly negative for CD4, CD8, CD30, and CD56. T-cell receptor gene rearrangements were positive for a clonal gamma T cell gene rearrangement.

Laboratory Data: Whole blood flow cytometry showed a CD4/CD8 ratio of 4.5. A Leukemia/Lymphoma Panel showed no abnormality. Serum T-cell receptor gamma gene rearrangement was negative. A CBC showed a WBC of 11.8 (slightly elevated) and platelet count of 456. A CMP showed no abnormalities. HIV and RPR tests were negative. However, PET/CT showed innumerable FDG-avid cutaneous lesions although no FDG-avid lymph nodes.

Clinical Course: The patient was treated with Prednisone 60mg daily and then tapered off as there was no improvement after 3 weeks. Methotrexate was added at a dosage of 17.5mg weekly. The patient continues to develop new lesions with persistence of older lesions.

Diagnosis: CD4-/CD8- T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorder (Probably Mycosis Fungoides or Primary Cutaneous CD8+ Aggressive Epidermotropic Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphoma)

Points of Emphasis: The histopathological features of skin with prominent epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes with clinically persistent plaques leads to a differential diagnoses that includes mycosis fungoides, primary cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. Often, these lesions can be differentiated by immunophenotyping with MF mostly showing a CD3+/CD4+/CD8-/BF-1+ phenotype, primary cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma showing a CD3+/CD4-/CD8-/BF-1- phenotype, and primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma showing a CD3+/CD4-/CD8+/BF-1+ phenotype. However, all three of these entities can show CD3+/CD4-/CD8-.

CD4/CD8 double-negative type MF has been commonly reported and has an indolent clinical course like that of typical MF. Primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma can be CD4-/CD8- in some cases. Finally, γ/δ T-cell lymphoma is usually CD4-/CD8-, but shows negativity for BF-1.

Our case showed a CD4-/CD8-/BF-1+ immunophenotype which excludes the diagnosis of a γ/δ T-cell lymphoma. However, the clinical course appears to be more aggressive due to the persistent plaques and multiple cutaneous FDG avid lesions. Therefore, an unusual CD8- primary cutaneous CD8+ aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma seems to be more likely than a CD4-/CD8- mycosis fungoides.

References:

1. Hodak E, David M, Maron L, Aviram A, Kaganovsky E, Feinmesser M. CD4/CD8 double-negative epidermotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: an immunohistochemical variant of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 276–284. 2. Toshinari Miyauchi, Riichiro Abe, Yusuke Morita, et al. CD4/CD8 Double-negative T-cell Lymphoma: A Variant of Primary Cutaneous CD8+ Aggressive Epidermotropic Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphoma? Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2015;95(8):1024-1025.

Case 2: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm- An Underrecognoized but Deadly tumor

Caregivers: Aditya Sood UG-2, Dipti Anand MD; Smyrna, GA; Atlanta, GA

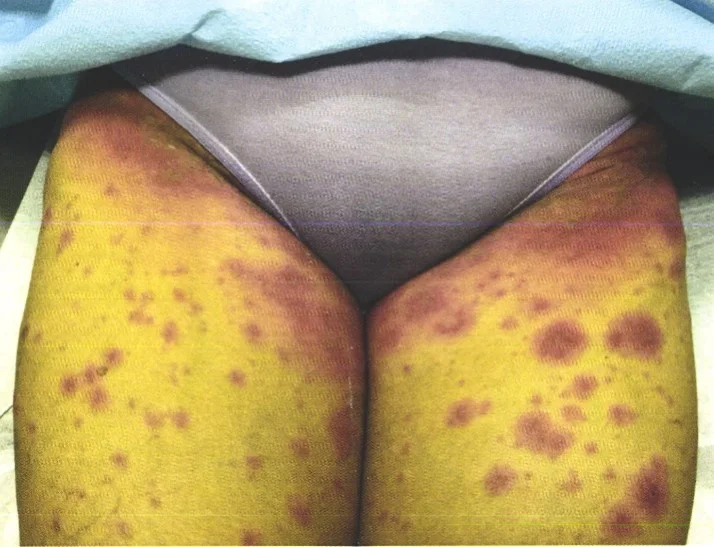

History: A 72 year old Caucasian male presented with acute onset of non-palpable, purpuric patches on left anterior proximal upper arm. This was clinically thought to be a bruise by physicians in an emergency room. The eruption did not resolve for ~2 months, and the patient was referred to dermatology.

Physical Examination: Physical examination showed an ecchymotic, bruised appearance of left arm with pigmented, purpuric patch and plaque. Clinical differential diagnoses included ecchymosis versus malignant melanoma.

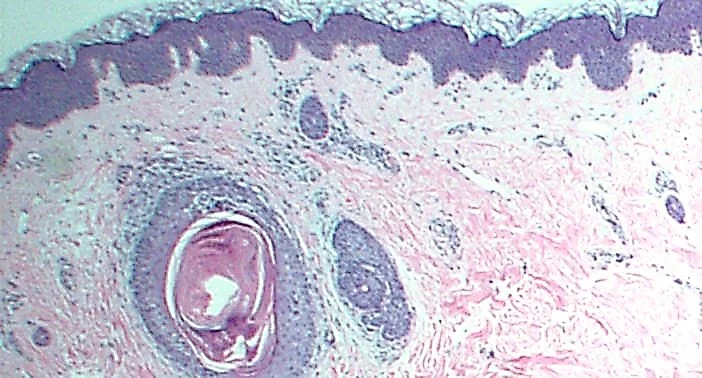

Histopathology: A punch biopsy showed diffuse effacement of the dermal architecture with a dense perivascular, periadnexal and interstitial infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli extending into the subcutis. Associated areas of dermal hemorrhage were seen. Immunophenotypically, the infiltrate was composed of CD45+ CD3- CD5- CD20- CD4+ CD8- CD56+ CD123+ TCL-1+ lymphoid cells, consistent with Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

Clinical Course: Patient was referred to a tertiary medical care center for work-up for systemic involvement and chemotherapy.

Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm (BPDCN).

Points of Emphasis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm (BPDCN) is a very clinically aggressive tumor derived from the precursors of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. It accounts for < 1% of all acute leukemia cases & 0.7% of cutaneous lymphomas. The male to female ratio for this tumor is ≥ 3:1. Most patients are elderly (mean age of 67 years at presentation).

Almost all cases have cutaneous lesions at presentation. Lesions can be solitary or multiple, presenting as, erythematous, violaceous or red-brown-nodules, tumors or plaques, with often a bruise-like appearance. There is a high frequency of bone marrow, peripheral blood (60–90%) and nodal (40–50%) involvement with leukemic dissemination.

In most cases, the neoplasm is confined to the skin at presentation. However, leukemic spread after variable, usually short, period of time is the rule, indicating that the primary cutaneous cases most likely represent “aleukemic” phase of leukemia cutis.

Initial responses to treatment are relatively common, but most patients relapse within a short space of time. It has a poor prognosis with median survival time of only 12–14 months (estimated 5-year survival is 0%). In 10–20% of cases, BPDCN is associated with, or develops into, a myelodysplastic syndrome, myelomonocytic leukemia or acute myeloid leukemia.

It is important to remember this very aggressive lymphoma with a high frequency of leukemic dissemination. Skin lesions are most often the first presenting manifestation of the disease. Cutaneous lesions can be bruise-like or pigmented simulating melanoma. Histology can pose a diagnostic challenge. Because of its aggressive behavior, it is important to correctly diagnose it in a timely fashion for proper clinical management.

References: 1. Wasif, R., Zhang, L., Horna, P., Sokol, L., Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendridic Cell Neoplasm: Update on Molecular Biology, Diagnosis, and Therapy, Cancer Control 291, Vol 21 No 4. , Oct. 2015 . 2. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008.

Case 3A: A Unique Case of Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma Mimicking Mycosis Fungoides

Casregivers: Michael James Davis, BMus, Dipti Anand, MD; Atlanta, GA

History: An 80-year-old Caucasian gentleman with no significant past medical or drug history presented with multiple acute and rapidly progressing lesions. No systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise or weight loss were reported.

Physical Exam: Exam revealed several 1-3 cm well demarcated, erythematous and violaceous plaques on both sun exposed and non-sun exposed aspects of the patient’s extremities and abdomen. No facial involvement was noted. Deep punch biopsies of the right anterior thigh, right posterior arm, and right anterior arm were performed.

Laboratory Data: ANA -, Anti Ro -, Anti La -, ESR 2.

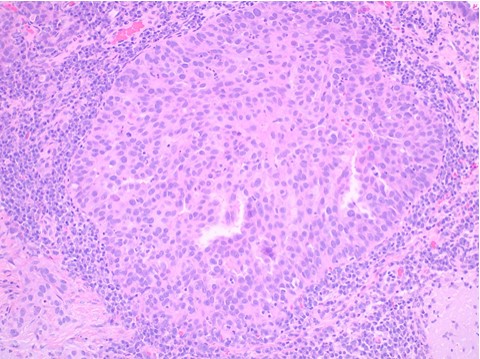

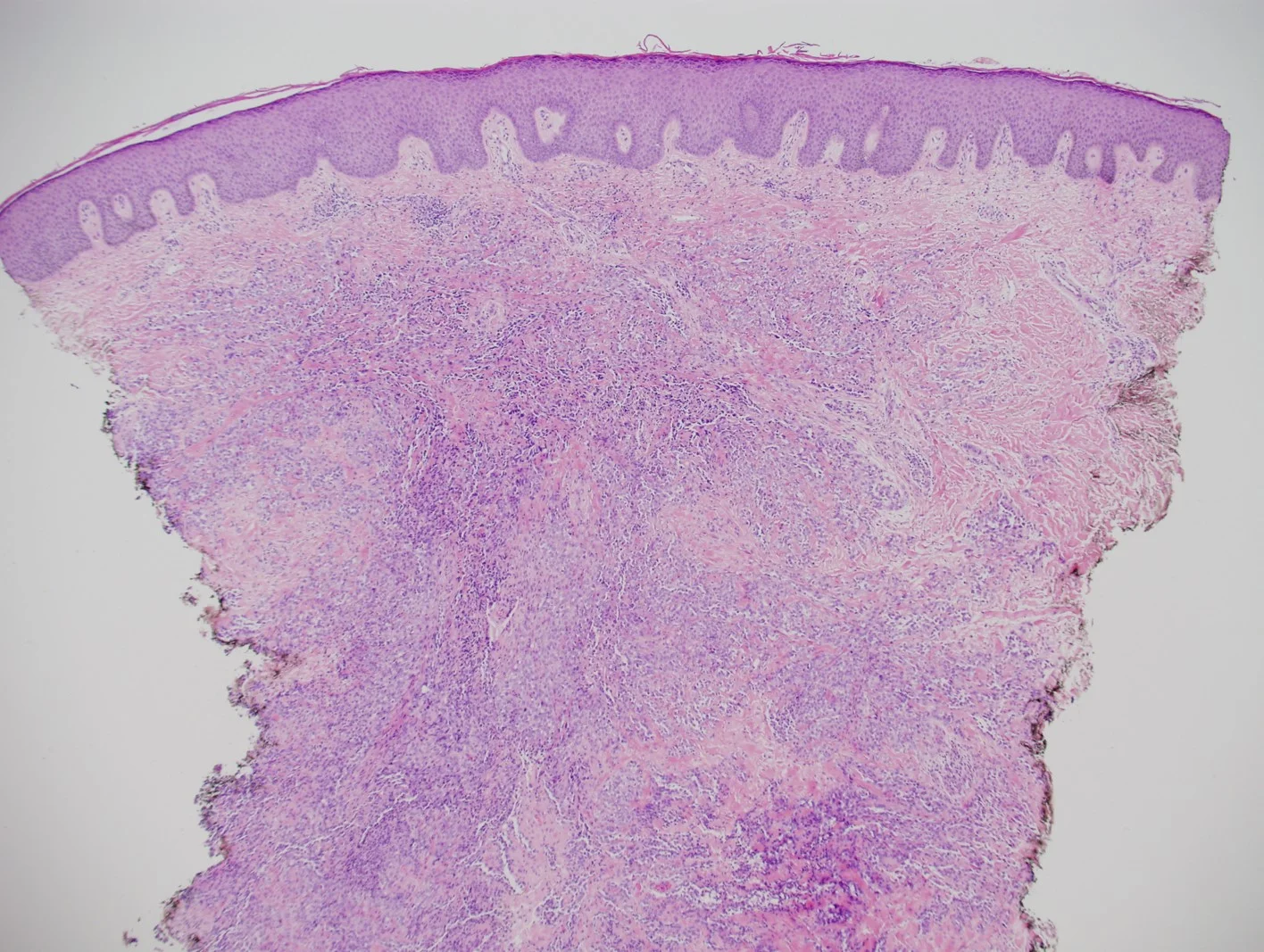

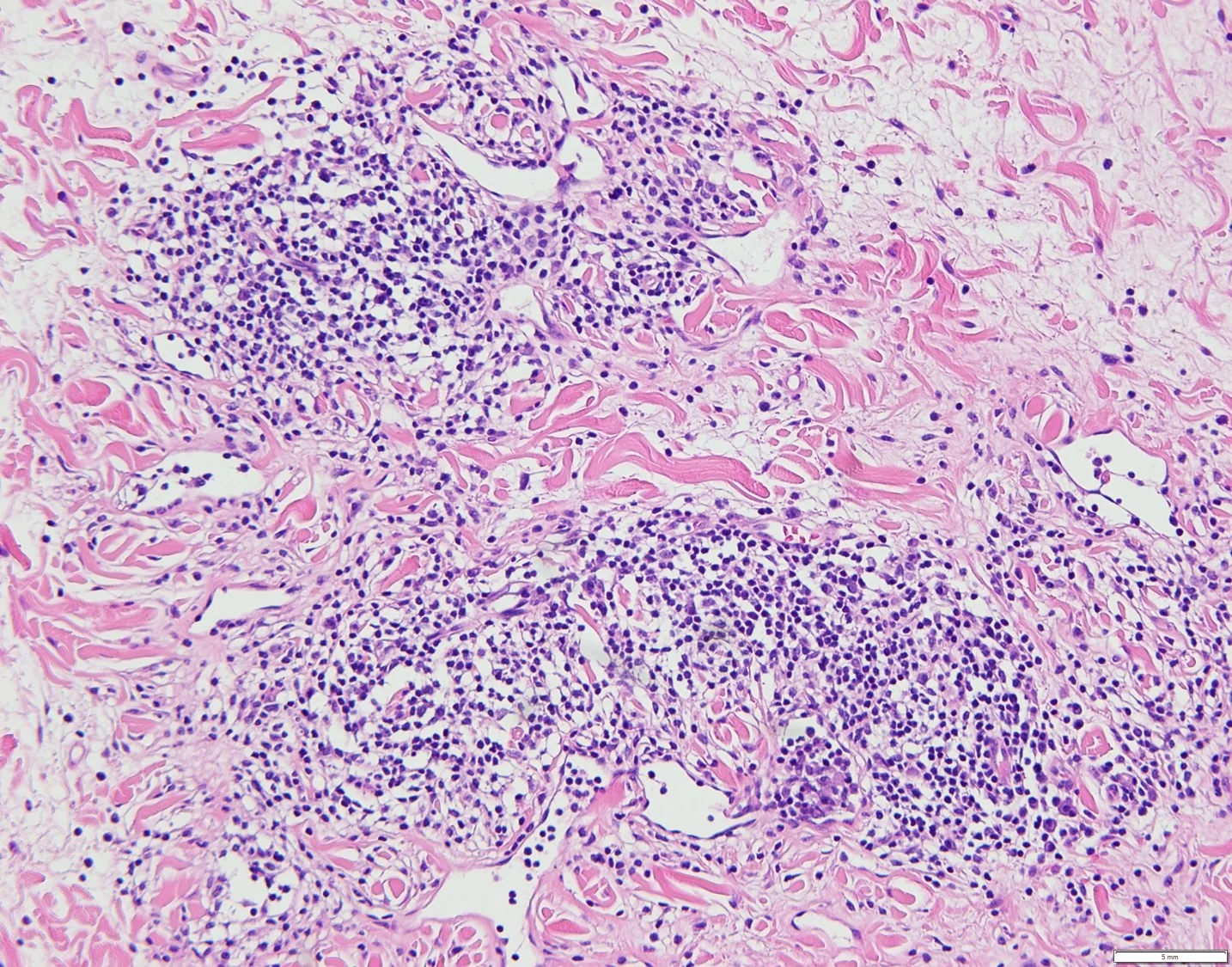

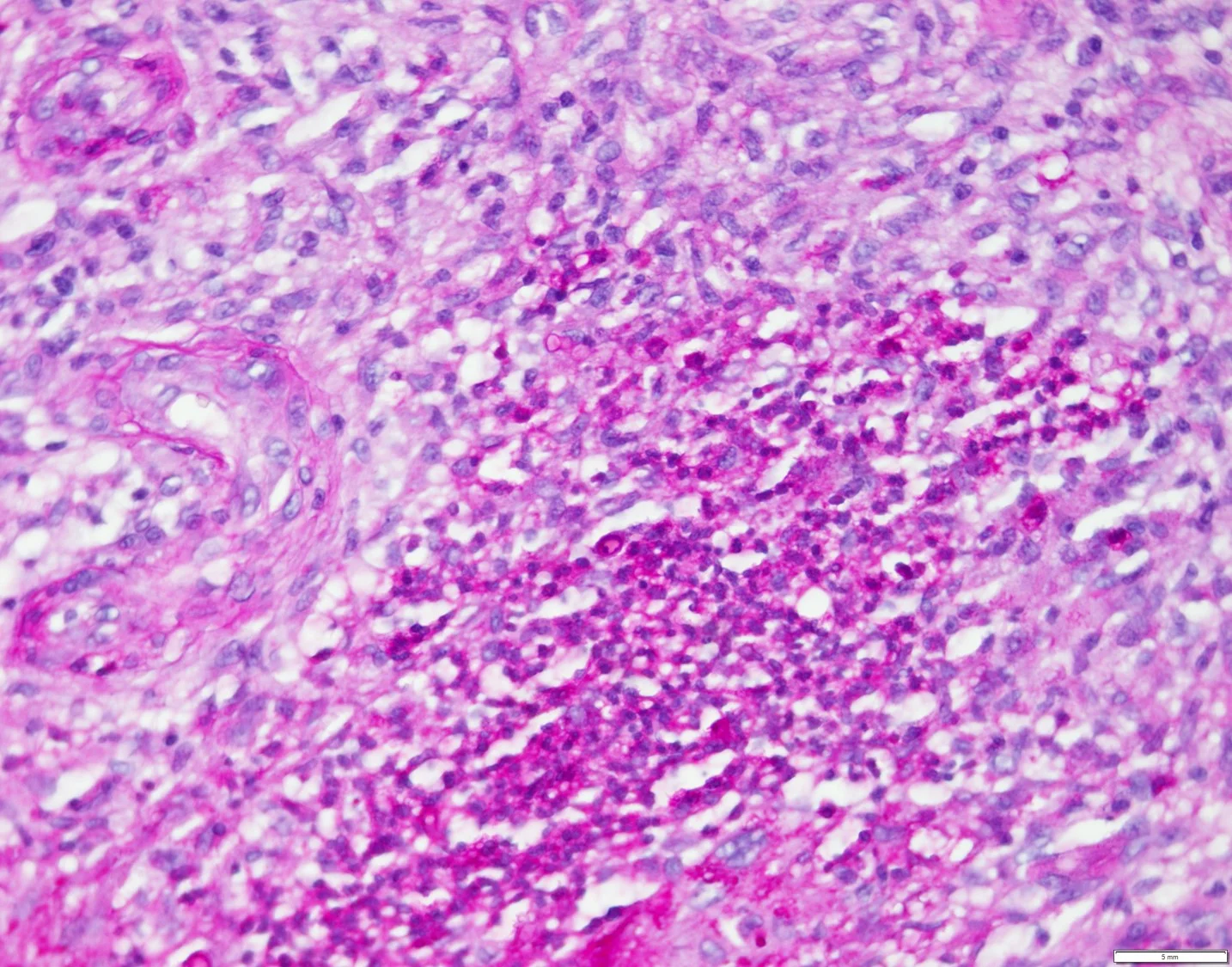

Histopathology: The sections showed a dense superficial and deep perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphoid infiltrate extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The lymphocytes were pleomorphic, intermediate to large, with irregular chromatin distribution and scattered mitoses. The overlying epidermis demonstrated subtle interface vacuolization with scattered single and collections of lymphocytes, suggestive of epidermotropism. There was no significant necrosis or vasculitis, but extravasation of erythrocytes with riming of fat by atypical lymphocytes was seen.

The histologic differential diagnoses included plaque and tumor stage mycosis fungoides, pseudolymphomatous lupus panniculitis, cytotoxic subcutaneous panniculitis-like-T-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous gamma/delta T cell lymphoma.

Immunohisochemical evaluation revealed tumor cells to be positive for CD2, CD3, CD56, TIA-1, and granzyme B, and negative for CD5, CD7, CD4, CD8, CD20, and CD123. Additionally, CD 30, Beta FI Gamma M1 were also negative. EBV-encoded RNA (EBER)-1 in situ hybridization was positive for EBV mRNA. RT-PCR T-Cell gene arrangement study was positive.

The histology and staining profile were consistent with EBV positive Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma.

Clinical Course: Systemic workup for nasopharyngeal and extra nodal site involvement was recommended at a tertiary care center.

Diagnosis: Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma.

Points of Emphasis: Beyond the classic presentation of an ulcerated mid facial tumor, previously coined “lethal midline granuloma,” Extranodal NK/T-Cell Lymphoma requires a high index of suspicion for accurate diagnosis. Following the nose and upper aerodigestive tract, the skin is the most commonly involved site. Lesions are typically plaques or nodules, at times ulcerated; vasculitis and panniculitis presentations can also occur. The infiltrate is usually angiocentric and may be angiodestructive with variably sized tumor cells.

Immunophenotypically, the tumor cells express CD2, CD3ɛ, CD56, TIA-1, and granzyme B. EBER in situ hybridization is the most reliable test for confirming the presence of Ebstein-Barr Virus which is detected in almost all cases. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma presenting in the skin is a highly aggressive tumor with a median survival of less than 15 months.

Our patient presented with a unique clinical and histologic manifestation of this uncommon lymphoma. Clinically, the lesions mimicked lupus panniculitis and mycosis fungoides, and lacked the tumor nodules and ulceration, often seen in this lymphoma. The histology also posed a challenge, simulating mycosis fungoides and pseudolymphomatous lupus erythematosus. The lymphoma lacked the necrosis, prominent angiocentricity and angiodestruction, and high mitotic rate with apoptosis, which is classic for this neoplasm. Epidermotropism as noted in our case is seen in ~30% of these tumors.

It is important for both clinicians and pathologists to be aware of this uncommon cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which can mimic mycosis fungoides both clinically and histologically. Awareness of this entity is important for its prompt recognition and treatment.

References: 1. Park, S, Ko, YH. “Epstein-Barr virus-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.” J Dermatol. 2014;41:29-39. 2. Peck, T, Wick, M. “Primary cutaneous natural killer/T-cell lymphoma of the nasal type: a report of 4 cases in North American patients.” Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:211-215. 3. Takata, K et al. “Primary Cutaneous NK/T-cell Lymphoma, Nasal Type and CD56-positive Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma: A Cellular and Clinicopathologic Study of 60 Patients from Asia.” Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1-12.

Case 3B: NK/T-Cell Lymphoma

Caregivers: Neeta Malviya BS, Juliet F. Gibson, MD, Yevgeniya Byekova Rainwater, MD; Dallas, TX

History: A 28-year-old male with a medical history of HIV infection presented with a 1-month history of a steadily enlarging, firm painful lesion on the right posterior shoulder. The lesion was initially diagnosed as an abscess with surrounding cellulitis and treated with multiple I&Ds in the emergency department with no improvement and progressive swelling of the right upper extremity despite numerous systemic antibiotics.

Physical Examination: Physical examination revealed a 15 cm yellow-brown, verrucous plaque on the right posterior shoulder with surrounding violaceous erythema and induration. Within 1 week, plaque ulcerated and developed an eschar.

Laboratory Data: Baseline laboratory studies revealed white blood cell count of 13 (reference range 4.22-10.33 cells/microliter), hemoglobin 11.5 (reference range 13.2-16.9g/dL), CD4 count of 507 (reference range 212-1403 cells/mm3), HIV viral load 111 copies/mL, negative blood and urine cultures, and wound cultures growing rare Acinetobacter lwoffi.

Histopathology: Histopathologic examination revealed an angiocentric and dermal proliferation of markedly atypical lymphoid cells with numerous mitoses and apoptotic bodies along with broad zones of necrosis. Atypical lymphoid cells highlighted with CD2, CD3, CD8, CD30, and CD56. CD20, PAX5, and CD4 stains were negative. In situ hybridization for Epstein Barr virus revealed positivity within nearly all atypical lymphoid cells. An ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy of the right axilla revealed morphologic and immunophenotypic findings consistent with a NK/T cell lymphoma.

Clinical Course: Computed tomography of the chest revealed a multicentric lymphoma producing a large right axillary mass and enlarging left paraspinous musculature. Nasal computed tomography did not reveal any masses. Bone marrow biopsy was found to be benign. Computed tomopgraphy of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an infiltration of the right gluteus medius and minimus muscles as well as the left paraspinous muscles at the level of the thoracolumbar junction. Overall lymphoma involvement included lymph nodes, multiple soft tissue sites including the right shoulder, back, left thigh and left knee. Two cycles of SMILE (steroid (dexamethasone), methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, and etoposide) chemotherapy were administered as per treatment protocol and the patient tolerated these well. This was followed with EPOCH therapy (Rituximab, etoposide, prednisolone, oncovin, cyclophosphamide, hydrocydanorubicin), which the patient also tolerated well and resulted in improvement of the shoulder lesion.

Diagnosis: NK/T-cell lymphoma.

Points of Emphasis: The cutaneous lesions from NK/T-cell lymphoma can often be initially mistaken for cellulitis as in the case of our patient. In a study of 41 cases of cutaneous extra-nodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, skin lesions presented in 3 different categories, nodular lesions, cellulitis or abscess-like swellings, and erythematous to purpuric patches (1). In the histopathologic analysis of these categories, it was found that tumor cell infiltration density was greater in cellulitis-like lesions or nodular lesions as compared to erythematous to purpuric patches. Both cellulitis-like lesions and nodular lesions are also more likely to display angiocentricity as was the case in our presented patient (1). The original cutaneous presentation in our reported case was of a cellulitis appearing lesion on the right arm, this later became necrotic in appearance and formed an eschar. The formation of an eschar is noted in one other case report of a 14-year-old boy with cutaneous involvement in NK/T-cell lymphoma (2). In distinguishing this lesion from cellulitis, failure of antibiotic treatment, progressive and widespread involvement of the cellulitis along with profound ulceration should prompt the clinician to explore an alternative diagnosis as well as suggest the possibility of NK-T cell lymphoma (3).

References: 1. Lee WJ, Lee MH, Won CH, Chang SE, Choi JH, Moon KC, et al. Comparative histopathologic analysis of cutaneous extranodal natural killer/T‐cell lymphomas according to their clinical morphology. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2015. 2. Xiao HJ, Li J, Song HM, Li ZH, Dong M, Zhou XG. Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive T/NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders Manifested as Gastrointestinal Perforations and Skin Lesions: A Case Report. Medicine. 2016;95(5):e2676. 3. Kim SH, Seon HJ, Choi YD, Yun SJ. Clinico-radiologic findings in primary cutaneous extranodal natural killer/t-cell lymphoma, nasal type mimicking cellulitis of the left arm. Iranian journal of radiology : a quarterly journal published by the Iranian Radiological Society. 2015;12(1):e12597.

Case 4A: Congenital Leukemia Cutis as Presenting Feature of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Caregivers: Caroline Lee, MD, Matthew LaCour, MS4, Jill Fruge, MD, Beverly Ogden, MD; New Orleans, LA, Baton Rouge, LA, Galveston, TX

History: ER is a 7 day old female infant who presented with non-pruritic blue to purple lesions over her trunk, neck, and extremities, first noticed at birth. She was born at 40 weeks and 3 days via Caesarean section after failed induction. This was her mother’s first pregnancy and pregnancy was without illnesses or complications. The patient was feeding well and having normal urine and stool output.

Physical Examination: Vitals: Temp: 98.5 degrees F, BP: 95/59mmhg, Pulse: 164, RR: 54, SpO2: 96%; Lymph nodes: negative for cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy

Abdomen: negative for hepatomegaly and splenomegaly

Skin: 2-4 mm red-violaceous papules distributed over abdomen, back, extremities and diaper area; violaceous nodules to right neck and on right foot

Laboratory Data: WBC count: 15.9 1000/ul (WNL), HGB: 13.7 gm/dl (WNL), HCT: 41.5 %, MCV: 102 fl (WNL), PLT count: 473 1000/ul (elevated), Differential: 50% neutrophils, 32% lymphocytes, 15% monocytes (elevated), 3% eosinophils, 1% basophils. No circulating malignant cells observed. CMP was unrevealing. LDH: 595 IU/L (elevated). Blood cultures were negative. Serologic studies for toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus were negative.

Histopathology: H&E: Malignant infiltrate of immature cells. Several immunostains were performed including CD45, CD34, CD117, myeloperoxidase, S100, CD68, CD79A, CD3, desmin, cytokeratin A, CD31, and CD43. The malignant cells are positive for CD34, CD68, CD43 and are negative for the other markers tested. These findings favor leukemia cutis/myeloid sarcoma over other small blue cell tumors.

Clinical Course: The hematology-oncology service was initially consulted and peripheral blood smear was found to be unremarkable. An infectious disease work-up was also unremarkable. The dermatology service was then consulted and the biopsy specimen was concerning for myeloid leukemia cutis. The patient was referred to St. Jude Children’s Hospital where further work-up was performed including a bone marrow aspirate which was consistent with acute myeloid leukemia. Cytogenetic analysis showed a CIC mutation in 15/20 metaphases. She completed Induction I chemotherapy including cytarabine, daunorubicin, etoposide (ADE) and Induction II chemotherapy with cytarabine, daunomycin, etoposide and intrathecal methotrexate, hydrocortisone, cytarabine. She is currently in remission and is completing the consolidation phase of chemotherapy

Diagnosis: Congenital leukemia cutis as the presenting feature of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Points of Emphasis: Infants born with a cutaneous eruption characterized by deep red to blue macules, papules and nodules are characterized as having a “blueberry muffin syndrome.”1-3 The most common causes of a blueberry muffin eruption include dermal erythropoiesis and neoplastic infiltrative diseases. An infant presenting with this eruption should undergo an extensive work-up to determine the underlying cause.2, 3 Hematopoiesis typically takes place in the skin from the first through fifth months of gestation.1, 2 Occasionally dermal erythropoiesis takes place during the neonatal period which may be due to an intrauterine viral infection, most commonly rubella, toxoplasmosis, or parvovirus, or due to congenital hematologic dyscrasias, including hereditary spherocytosis, twin-twin transfusion syndrome, or hemolytic disease of the newborn. Infants should also be evaluated for neoplastic infiltrate diseases including metastatic neuroblastoma, histiocytic disorders and congenital leukemia.1-4

Congenital leukemia encompasses all cases diagnosed from birth to 6 weeks of life with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) denoted as the most common type. The etiology of congenital leukemia is unknown, but it has been associated with maternal exposure to radiation, bioflavonoid, tobacco and illicit drugs, topoisomerase II inhibitors, such as coffee, tea, cocoa, wine (catechins), and soy products (genistein), high birth weight (>4000 g), high levels of insulin-like growth factors, and disorders such as Down syndrome. Infants with congenital leukemia may present with varying signs and symptoms, with leukemia cutis presenting in 25-30% of cases.3, 4

Leukemia cutis (LC) represents a cutaneous neoplastic leukocytic infiltrate and may be the presenting sign of an underlying leukemia.1,3,5 Patients with LC at birth can have variable cutaneous manifestations but most commonly present with multiple firm blue, red, or purple papules, nodules, or plaques that give rise to a “blueberry muffin” appearance.1, 3 Leukemic skin symptoms are most commonly noted in patients with AML that have a prominent monocytic or myelomonocytic component. Rarely, cutaneous involvement by a leukemic infiltrate can occur without concurrent bone marrow or peripheral blood involvement by acute leukemia, which is referred to as aleukemic LC.6

Diagnosis of leukemia cutis is confirmed by the pattern of skin infiltration, specific histomorphology, and the immunohistochemical staining pattern of the cells. Histology should be correlated with the clinical presentation and peripheral blood and bone marrow findings.7 LC may show different patterns of infiltration. The most common presentation includes a dense diffuse dermal infiltrate of pleomorphic leukemic cells arranged in a linear array between collagen bundles in the reticular dermis. The infiltrate may also commonly present in a periadnexal or perivascular fashion. Typically, infiltrates diffusely extend into the dermis and subcutis but spare the epidermis resulting in a Grenz zone. Malignant myeloid cells are numerous, and nuclear characteristics may range from markedly atypical folded or reniform nuclei to monomorphous and cytologically bland nuclei.1, 3, 4 Immunohistochemical analysis is required for confirmation. Malignant cells are negative for CD3 and CD20, effectively ruling out a lymphocytic process. Most commonly in myeloid leukemia cutis, cells will be CD43+/myeloperoxidase (MPO)+ or CD43+, MPO-, CD68+, CD56-, CD117-.1,5 A recent cohort study by Cronin et al detailing the approach to diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis found that CD43 was positive in 97%, myeloperoxidase was positive in 42%, CD68 was positive in 94%, CD163 was positive in 25%, and CD56 was positive in 47% of those diagnosed with myeloid LC.5 They point out that when myeloperoxidase staining was negative CD43 and CD68 were both positive.5

Since LC indicates a systemic leukemia, treatment of the underlying leukemia typically resolves the cutaneous eruptions of LC. Referral and close follow up with Hematology-Oncology should be implemented. Unlike LC in adults that denotes extramedullary involvement and poor prognosis, LC secondary to congenital leukemia does not denote a worse prognosis. Regardless, congenital leukemia due to AML has a poor prognosis with some reports of survival rates as low as 26%, thus rapid diagnosis and treatment is essential to improve mortality.3,4

References: 1. Weedon J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th edition. Charlottesville (VA): Elsevier Saunders; 2016. 2. Gottesfeld E, Siverman R, Coccia P, Jacobs G, Zaim M. Transient blueberry muffin appearance of a newborn with congenital monoblastic leukemia. J AM Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:347-51. 3. Zhang I, Zane L, Braun B, Maize J, Zoger S, Loh M. Congenital leukemia cutis with subsequent development of leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Feb; 54(2 Suppl):S22-7. 4. Choi JH, Lee HB, Park CW, Lee CH. A Case of Congenital Leukemia Cutis. Annals of Dermatology. 2009;21(1):66-70. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.1.66.

Case 4b: Leukemic Infiltrate Secondary to Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Caregivers: Carole Bitar, MD, Carole Bitar, MD; Jacqueline Witt, MS; Jalal Maghfour, MS; New Orleans, LA

History: This is a 45-year old woman with past medical history of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) on nilotinib that was admitted to the hospital for progressive swelling and severe pain of her left leg. The process started 6 days previously when she initially noticed a “knot” under her skin that was itchy then it became red and swollen. She experienced pain and burning sensation in that area. The patient noted that she experienced chills and subjective fever at home. She denied any trauma. Doppler ultrasound was unremarkable and there were no signs of DVT. She was started on clindamycin for presumed cellulitis and started to improve with decrease redness and swelling although there was a persistent subcutaneous nodule on the left leg. The subcutaneous nodule had a greenish discoloration. The patient reported that additional green subcutaneous nodules appeared on the right arm. She had a past history of leukemia cutis with abundant blasts in 2017 for which she was treated with induction chemotherapy. On this admission, she was started on hydroxyurea and nilotinib.

Current Medications: Clindamycin, hydroxyurea, nilotinib, pantoprazole.

Physical Examination: There is an erythematous plaque over the left shin, tender to touch and warm with a centrally located greenish subcutaneous nodule. Two subcutaneous greenish nodules over the right arm were present.

Laboratory Data: Two punch biopsies were performed over the left leg for hematoxylin and eosin stain and for flow cytometry. Laboratory work up was significant for very high WBC of 167x103. Bone marrow biopsy showed chronic myeloid leukemia with no blasts.

Histopathology: A punch biopsy showed an atypical perivascular infiltrate comprised of neutrophilic, eosinophilic, and mononuclear cells compatible with immature myelocytes involving the dermis and subcutis with hemorrhagic lobular panniculitis. The infiltrate was not blastic but was compatible with leukemic infiltrate secondary to chronic myelogenous leukemia. The majority of perivascular cells stained positive for CD68. Myeloperoxidase stained numerous cells compatible with myelocytes. ERG immunostain confirms the presence of endothelial cells.

Flow cytometry: Nucleated cellularity consists predominantly of granulocytic cells. While there is a minute population (1.6%) of CD34+ cells falling within a typical blast gate by CD45/side scatter, these do not form a discrete cluster on examined histograms. It is noted that this patient's prior cutaneous leukemia involvement reportedly manifested as a mixture of mature and immature cells; therefore, morphologic correlation is essential.

Clinical Course: The patient continues to be followed by hematology/oncology and maintain current medication regimen. She is hesitant to undergo the recommended induction chemotherapy.

Diagnosis: Leukemic infiltrate secondary to chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Points of Emphasis: Leukemia cutis is a broad diagnosis for all cutaneous manifestations of leukemia caused by either myeloid or lymphocytic infiltrates to the skin. Although most frequently associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), it has also been described in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Typically, a diagnosis of leukemia predates skin involvement, but rarely, skin disease may be the first indication of systemic disease. Roughly 10-15% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia are diagnosed with leukemia cutis. In comparison, up to 25-30% of infants with congenital leukemias have skin involvement, the majority of which are associated with AML. Almost half of adult patients with acute myelomonocytic and monocytic subtypes of AML will develop skin manifestations1. Between 4 and 20% of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma patients have cutaneous involvement and 20-70% of mature T-cell leukemias involve the skin. Rarely do precursor B- or T-cell lymphoblastic leukemias and lymphomas or plasma cell myelomas involve the skin1.

Patients present with violaceous and erythematous papules, nodules, and plaques. Often manifesting at points of previous or current inflammation, the lower extremities are most frequently affected1. Rarely, clinical features described as leonine faces have been reported in a subset of leukemia cutis patients as well as panniculitis mimicking erythema nodosum. Close to a third of children with leukemia cutis will demonstrate the classic “blueberry muffin” appearance. Higher levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase and ß2-microglobulin have been reported in patients with leukemia cutis versus those with leukemia without cutaneous manifestations. No other clinical or demographic associations have been reported1.

Histopathologically, leukemia cutis demonstrates perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue without involvement of the upper papillary dermis. Immunophenotyping is crucial to diagnosing leukemia cutis, as pathology is often non-specific. Important stains such as myeloperoxidase and lysozyme are also important for identifying myeloid cells2. The neural cell adhesion molecule CD56 is important for identifying AML, although its sensitivity has been debated. Other molecules such as CD68/KP-1 and CD117 are also valuable in identifying AML.

Myeloid sarcoma, also known as granulocytic sarcoma, is a cutaneous manifestation of malignant myeloid cells and therefore a subset of leukemia cutis. It is also classically referred to as “chloroma” because of the greenish hue from the enzymatic function of myeloperoxidase3. Myeloid sarcoma is most commonly associated with AML and occurs in 2-3% of those patients3. It very rarely appears in CML patients mainly in the setting of blastic transformation.

The prognosis and treatment of leukemia cutis relies on addressing the underlying disease. Many reports suggest that by the time the disease manifests itself in the skin, the patient’s prognosis is poor. It has been reported that 88% of patients will die within 1 year of diagnosis of leukemia cutis1. This poor prognosis has been attributed to an associated blast transformation and crisis indicative of disease progression and often accompanying the presentation of leukemia cutis. Interestingly, patients with leukemia cutis secondary to a congenital leukemia do not have such a poor prognosis.

References: 1. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008 Jan;129(1):130-42. 2. Wang YN, Lian CG, Hu N, Jin HZ, Liu YH. Clinical and pathological features of myeloid leukemia cutis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(2):216-21. 3. Vasconcelos ERA, Bauk AR, Rochael MC. Cutaneous myeloid sarcoma associated with chronic myeloid leukemia. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 Suppl 1): 50-2.

Case 5A: Atypical Spitz Nevus in a 3-Year-Old

Caregivers: Margaret Snyder, Weston Wall MD, Daniel J. Sheehan MD, Loretta S. Davis MD; Augusta, GA

History: A 3-year-old girl with no family history of skin disease presented to dermatology with a 2-year history of a growth on her left earlobe. The mother stated that the growth periodically changed in size, sometimes enlarging and other times shrinking.

Physical Examination: Physical examination revealed a flesh-colored 3x4mm papule on the left earlobe.

Histopathology: Initial Shave Biopsy: Compound proliferation of enlarged spitzoid melanocytes, involving the deep edge of the biopsy. Molecular analysis of the specimen via the Affymetrix Oncoscan Microarray system revealed mosaic loss of chromosomes 9 and 14, a finding inconsistent with pediatric spitzoid melanoma and supportive of classification as an “atypical spitz tumor.” Re-excision was recommended. Final resected specimen: Pan-Melanoma cocktail revealed microscopic foci of residual compound Spitz tumor, with negative resection margins.

Clinical Course: Plastic surgery excised the residual lesion, achieving negative margins. Patient has since been seen by dermatology and plastic surgery, with well-healing cicatrix and negative recurrence at 11 months.

Diagnosis: Atypical Spitz Nevus

Points of Emphasis: Spitz nevi are uncommon melanocytic neoplasms seen in the pediatric population. These lesions are classified on a spectrum of increasing severity from typical Spitz nevus to atypical Spitz nevus to atypical Spitz tumor to spitzoid melanoma. Due to significant dermoscopic and histopathological overlap throughout the spectrum, precise diagnosis remains difficult and unstandardized. Intermediate categories of “atypical Spitz nevi” and “atypical Spitz tumor” show more marked atypical features than typical Spitz nevi, but do not meet the criteria to be classified as spitzoid melanoma. The malignant potential of intermediate categories is therefore uncertain, resulting in a lack of consensus among dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and pathologists regarding treatment. Indeed, there currently exists no algorithmic approach to atypical Spitz nevi or atypical Spitz tumor.

References: 1. Abboud J, Stein M, Ramien M, Malic C. The diagnosis and management of the Spitz nevus in the pediatric population: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 13;6(1):81 2. Ferrara G, Gianotti R, et al. Spitz nevus, Spitz tumor, and spitzoid melanoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic overview. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):589-98, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.012. 3. Metzger A, Kane A, et al. Differences in Treatment of Spitz Nevi and Atypical Spitz Tumors in Pediatric Patients Among Dermatologists and Plastic Surgeons. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Nov;149(11):1348-50. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4947.

Case 5B: Pigmented Spindle Cell (Reed’s) Nevus with Chromosomal Mutations

Caregivers: Osama Hashmi MPH, Jack Yu, MD, Daniel Sheehan, MD; Augusta, GA

History: A 13 year old Hispanic male presented to his pediatrician for an annual checkup. He has no significant medical, birth, or social history. He noted a raised black lesion on his right arm which has been enlarging over the past five years. There was no personal or family history of melanoma. Patient also denied any pain, itching or bleeding with the lesion.

Physical Examination: Physical exam revealed a 7mm irregular darkly pigmented papule on the right arm with an irregular border. The papule was excised by plastic surgery.

Laboratory Data: Not applicable.

Histopathology: There is a well circumscribed proliferation of moderately enlarged spindled melanocytes, arranged mostly as nets along the dermoepidermal junction. There is coarsely papillated epidermal hyperplasia. The junctional melanocytes have scant, pigmented cytoplasm and small monomorphous oval nuclei. Smaller, more oval and less pigmented cells are present in the subjacent papillary dermis. There is pigmentation of the basal layer and in subjacent melanophages. DNA analysis was performed using the Affymetrix Oncoscan Microarray system. BRAF600VE mutation was not identified on the specimen. Mosaic losses were identified on chromosomes 6 (6q22.1q27) and 15 (15q11.1q21.2) including MYB.

Clinical Course: No recurrence of the lesion has been noted.

Diagnosis: Pigmented Spindle Cell (Reed’s) Nevus with NTRK3 or ROS1 gene fusion

Points of Emphasis: Pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed is a variant of Spitz nevus and can be clinically and histologically challenging to distinguish from melanoma. BAP1, ALK, NTRK1, NTRK3, BRAF, ROS1, and HRA have been associated with Spitz nevus and literature has shown these genetic mutations to be specific to spitzoid neoplasms, distinguishing them from nonspitzoid melanoma, blue melanocytic lesions, and deep penetrating nevi. In this case, a genetic mutation was identified on chromosomes 6 and 15. Chromosome 15 is a known location for the NTRK3 gene and chromosome 6 is a known location for the ROS1 gene. This case illustrates possible genomic mutation that can be found in this variant of Spitz nevus.

References: 1. Urso, Carmelo. "Spitzoid Neoplasms: Suggestions from Genomic Aberrations." Dermatopathology 5.1 (2018): 26-29. 2. VandenBoom T, Quan V, Gerami P, et al. Genomic Fusions in Pigmented Spindle Cell Nevus of Reed. American Journal Of Surgical Pathology [serial online]. August 2018;42(8):1042. 3. Lee CY, Sholl LM, Zhang B, et al. Atypical Spitzoid Neoplasms in Childhood: A Molecular and Outcome Study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(3):181-186. 4. Amatu, Alessio, Andrea Sartore-Bianchi, and Salvatore Siena. "NTRK gene fusions as novel targets of cancer therapy across multiple tumour types." ESMO open 1.2 (2016): e000023.

Case 6: A Case of Desmoplastic Malignant Melanoma: A Diagnostic Pitfall

Caregivers: Michael James Davis, BMus, Dipti Anand, MD; Atlanta, GA

History: A 66-year-old Caucasian woman presented for her routine physical examination and was found to have a lesion on her left upper arm. Physical examination and review of systems were otherwise negative.

Physical Exam: A 0.5 x 1.0 cm poorly defined, asymmetric pink plaque with irregular borders and subtle dotted vessels was present on the left upper arm. A shave biopsy with the clinical impression of basal cell carcinoma vs squamous cell carcinoma was performed.

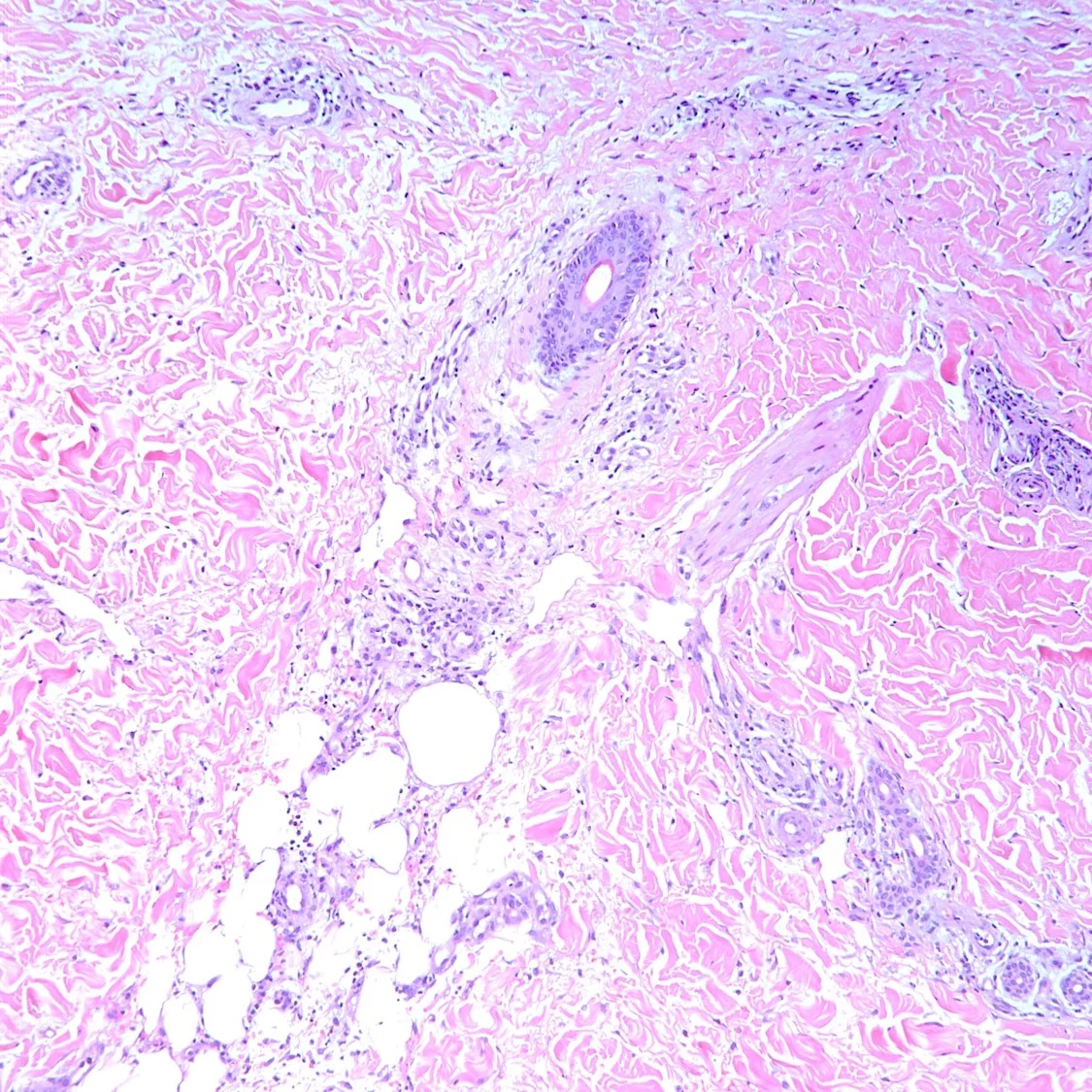

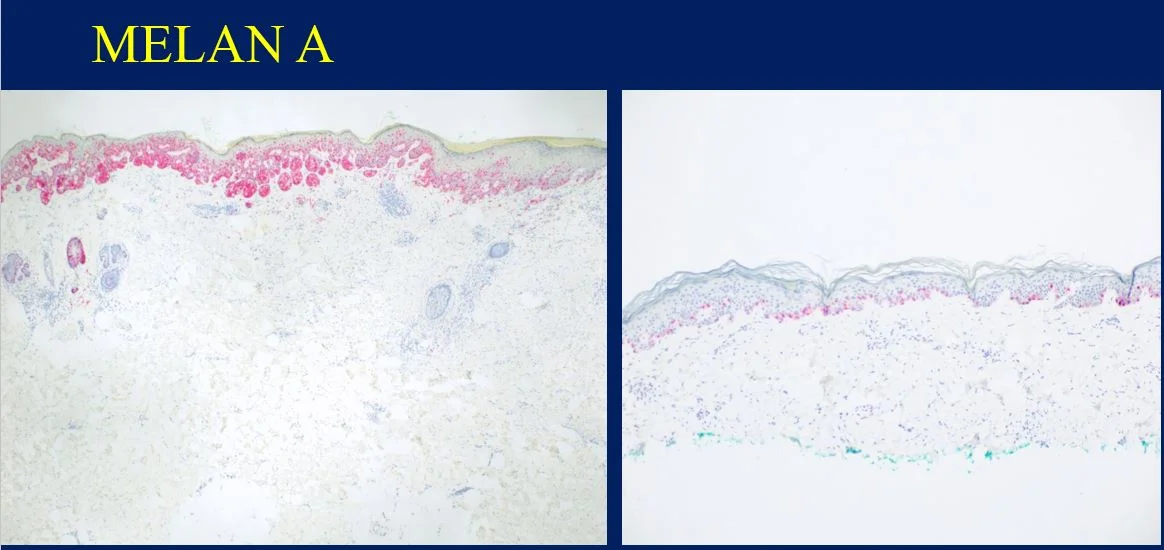

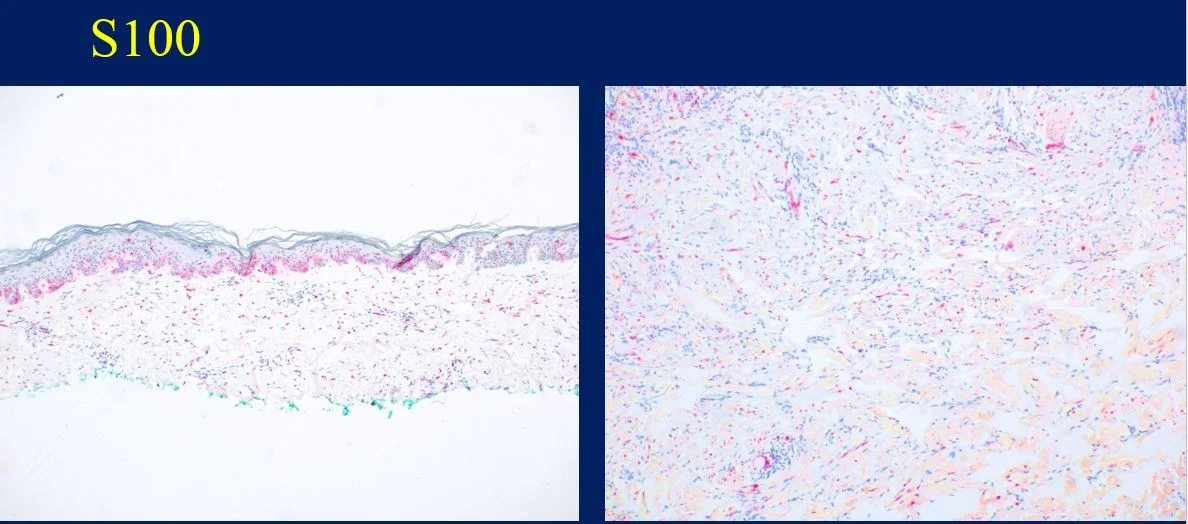

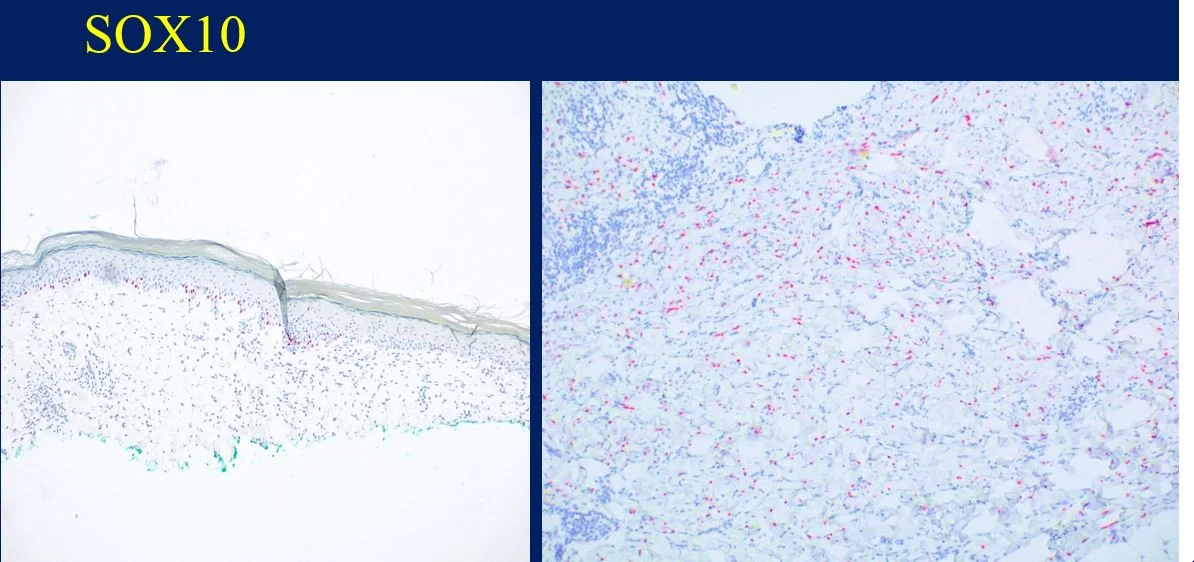

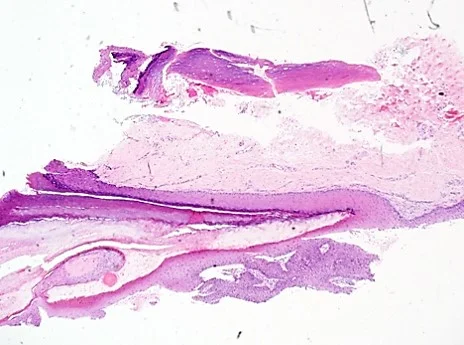

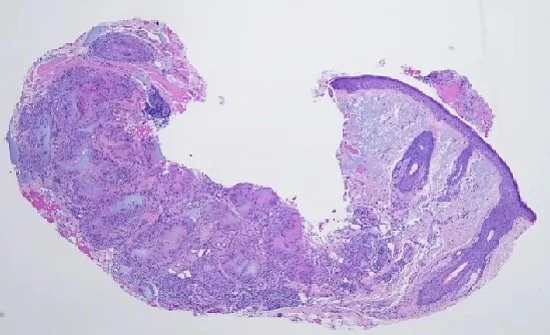

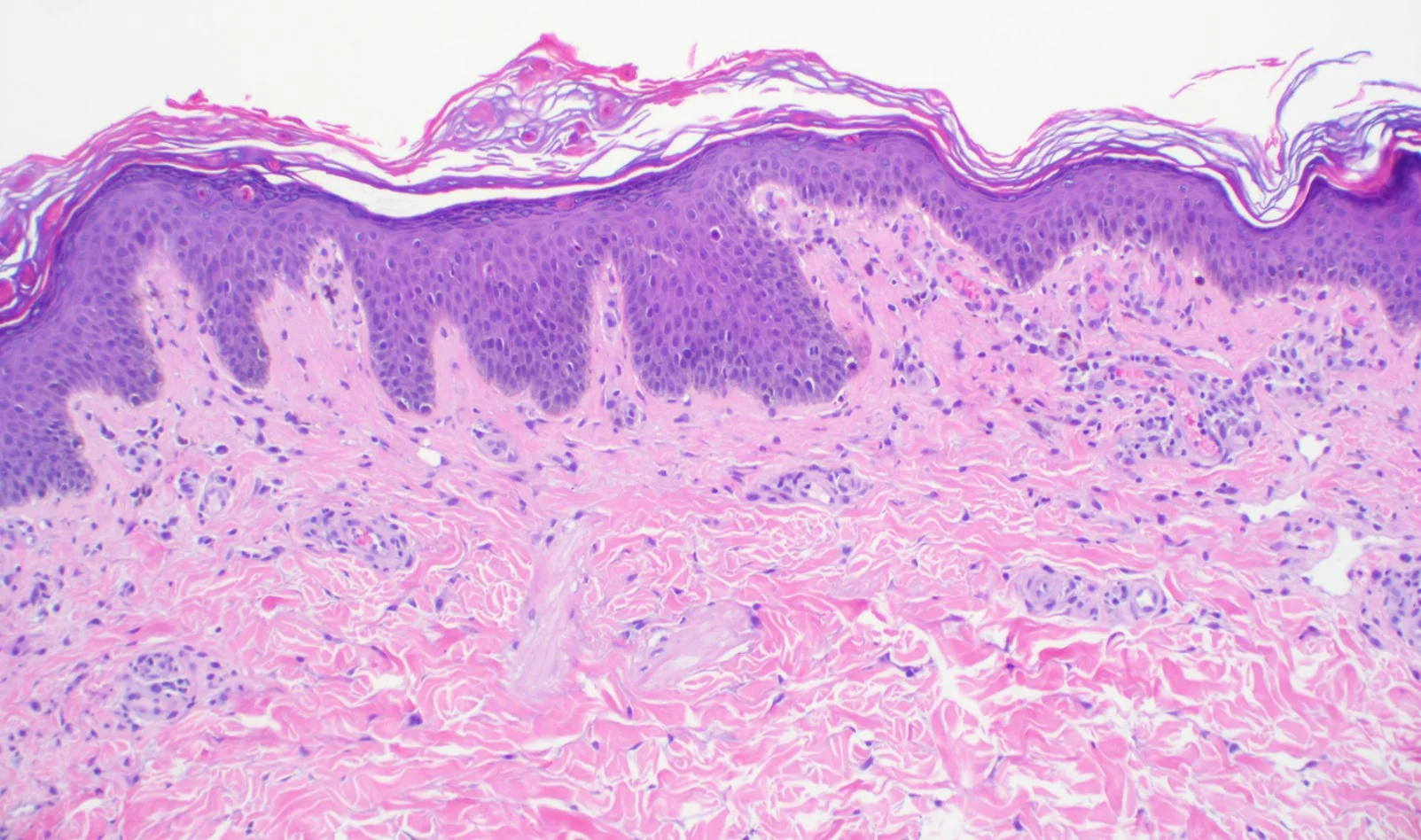

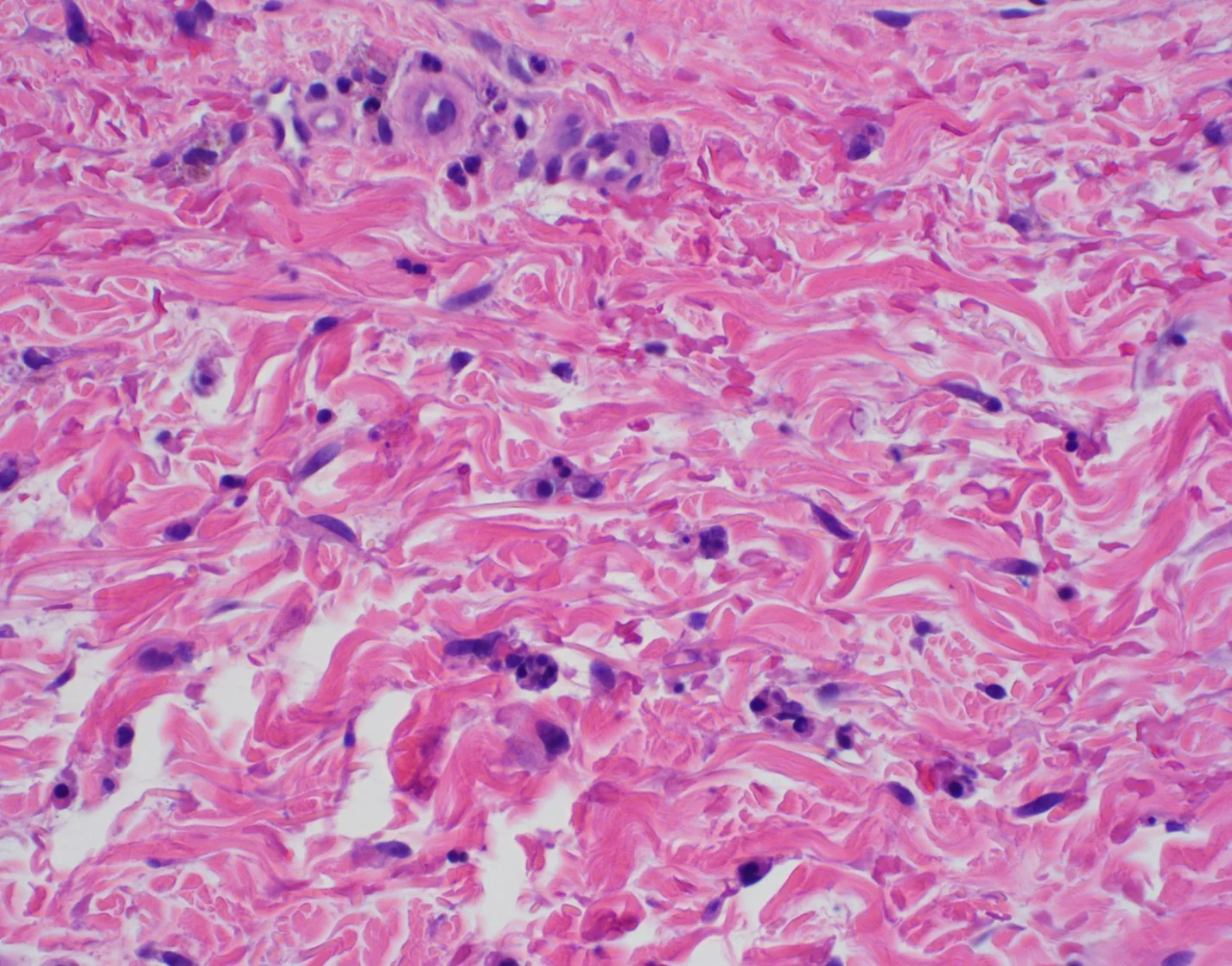

Histopathology: Histology showed dermal scarring with stromal perivascular lymphocytic inflammation, and slight junctional melanocytic proliferation. S-100, Melan-A and SOX-10 immunohistochemical markers highlighted the patchy atypical junctional melanocytic proliferation, with S-100 and SOX-10 also showing focal and weak staining of the dermal spindle cells. Additional information revealed no prior history of biopsy at this site. The pathology was signed out as “atypical compound melanocytic proliferation with scar” with recommendation for complete removal of the lesion and correlation with the residuum in the re-excision specimen.

A full thickness re-excision of the site showed, in association with scar of the previous procedure, classic appearing melanoma in-situ with lentiginous, contiguous junctional melanocytic proliferation of single and nests of enlarged, atypical melanocytes. In the dermis was a diffuse proliferation of cytologically banal, delicate spindle cells with mildly enlarged and slightly hyperchromatic nuclei and occasional dermal mitoses (~2/mm2). Associated trailing lymphoid aggregates were noted in the stroma. S-100 and SOX-10 diffusely highlighted the dermal melanocytic proliferation which was negative for Melan-A.

Diagnosis: Invasive Malignant Melanoma, Desmoplastic type, with a Breslow thickness of 2.1 mm, Clark’s level 4, and with a pathologic tumor stage of pT3a.

Points of Emphasis: Desmoplastic Melanoma (DM) is a rare cutaneous malignancy that proves a challenge for both clinicians and pathologists because of its subtle presentation and broad differential diagnosis. It is typically found on chronically sun-damaged skin of older individuals and has a male to female ratio of approximately 2:1. DM often presents as an amelanotic plaque or an ill-defined scar-like lesion that lacks an epidermal component; it can also be found in the background of other melanomas, most commonly lentigo maligna melanoma. Compared to conventional melanoma, DM has both a lower rate of nodal metastasis despite greater median tumor thickness at presentation and a relatively higher incidence of local recurrence.

Histologically, DM remains a challenging diagnosis and necessitates a high index of suspicion. Atypical spindle cells are found in a densely hyalinized collagenous stroma. There can be deep infiltration and invasion into the subcutis, and DM has a high propensity for perineural invasion. Trailing lymphoid aggregates can be a subtle clue in reaching the diagnosis. An important pitfall to appreciate is that DM can be negative for melanocytic markers including Melan-A, Mart-1, and HMB-45. In this case, the tumor was negative for Melan-A.

References: 1. Han, D et al. “Clinicopathologic Predictors of Survival in Patients with Desmoplastic Melanoma.” PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119716. 2. Chen LL, BA, Jaimes, N, Barker CA, Busam KJ, Marghoob, AA. “Desmoplastic melanoma: A review.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

Case 7: Ectopic Extramammary Paget’s Disease Presenting on the Face- An Extraordinary Case

Caregivers: Dipti Anand, MD, Aditya Sood, UG-3; Athens, GA and Atlanta, GA

History: An 81 year old Caucasian male with past medical history of gastric adenocarcinoma (diagnosed in March 2015), on systemic chemotherapy with capecitabine (Xeloda), presented with a pink plaque on his right cheek.

Physical Exam: A 2 cm erythematous, scaly plaque was noted on the right cheek. The clinical impression was a basal cell carcinoma.

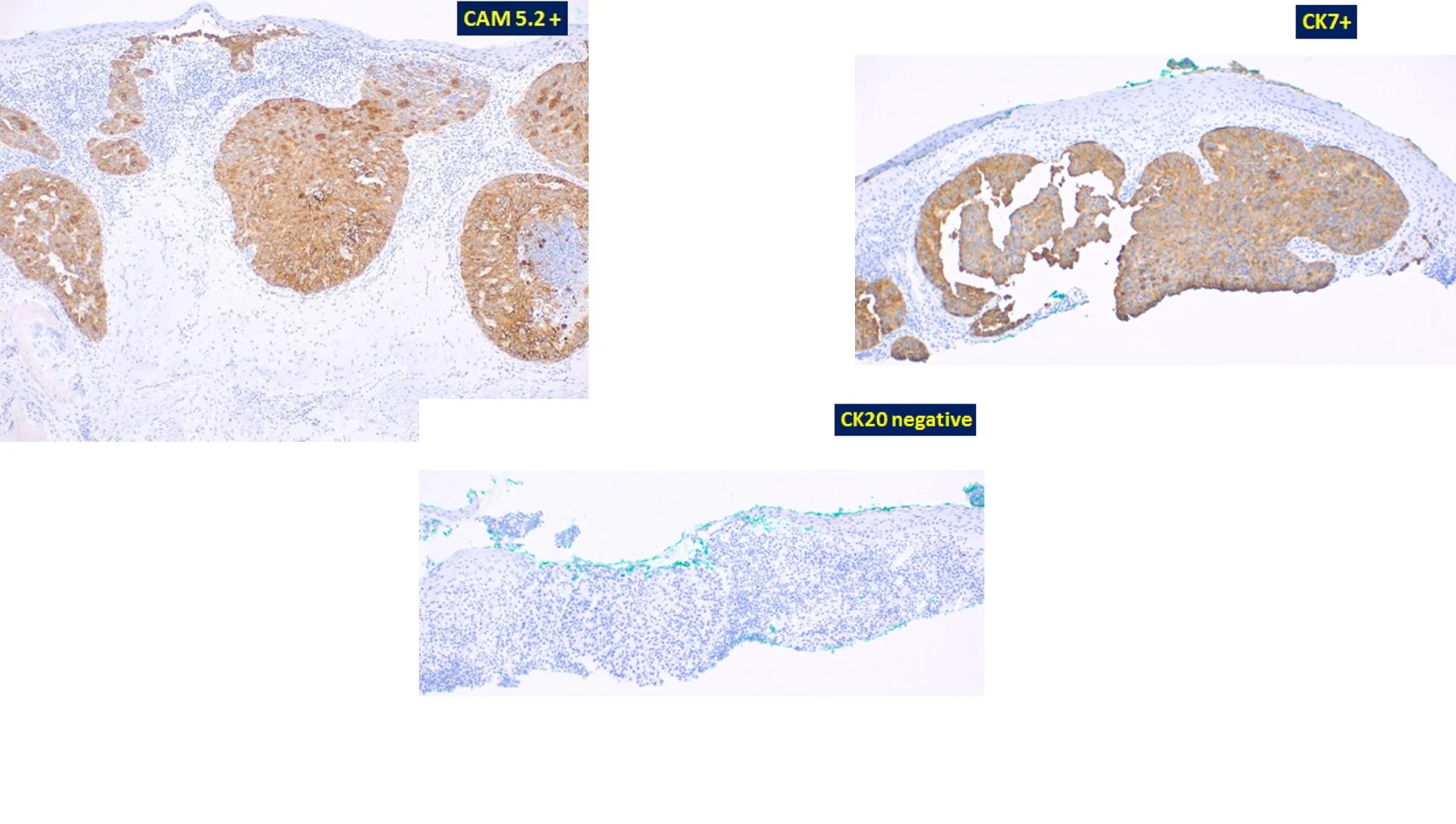

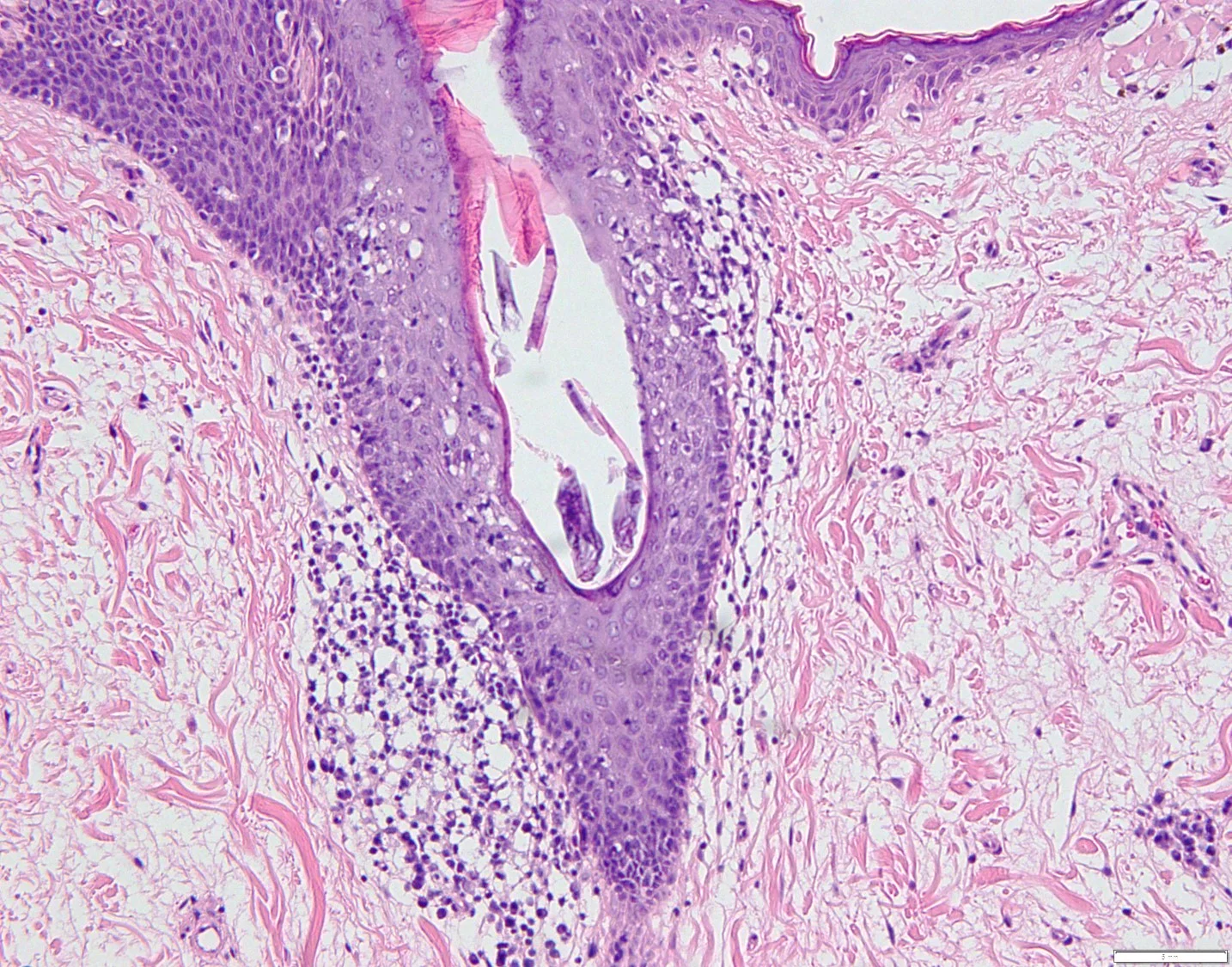

Histopathology: An initial shave biopsy from the lesion showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma located in the dermis, exhibiting focal contiguity with the overlying epidermis. The histology and immunophenotype of the tumor (p63- and CK7+) were most consistent with an adenocarcinoma, either primary cutaneous or an epidermotropic metastasis of a visceral carcinoma. As only a portion of the lesion was available for evaluation, complete excision and correlation with the residuum in the re-excision was recommended for a definitive diagnosis. Subsequent excision of the neoplasm showed a broad, poorly circumscribed proliferation of epithelial cells with abundant pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and enlarged nuclei partially replacing the epidermis and involving some follicular infundibular units. Pagetoid scatter of the tumor cells was also noted. Aggregates of similar appearing cells were present in the superficial dermis. The neoplasm on repeat staining was confirmed to be p63 negative and Cytokeratin7, EMA and CAM 5.2 positive. A concomitant review of the patient’s original gastric tumor, showed distinct histologic features with columnar cells and hyperchromatic nuclei, unlike most of the cells in the current facial lesion. The cheek tumor was favored to represent “Extramammary Paget’s disease”, possibly an adenocarcinoma arising in Bowen’s disease. One could consider a metastatic epidermotropic adenocarcinoma, but the breadth, poor circumscription and very extensive intrafollicular component were considered unlikely histologic presentations of a visceral metastasis to the skin.

The lesion was adequately excised and the patient reports no subsequent recurrences over a period of 5 months.

Points of emphasis: Extramammary Paget's disease (EMPD) is a rare neoplasm mostly affecting apocrine gland bearing skin[1]. Although primarily seen in the anogenital area, the tumor can also rarely appear in non-apocrine bearing skin and is referred to as “ectopic extramammary Paget's disease” [2]. It is important for dermatopathologists to be aware of this rare variant of EMPD as it can histologically mimic primary cutaneous malignancies, especially Bowens disease and melanoma. Adequate immunohistochemical analysis aids in its diagnosis. The diagnosis also necessitates the need for a complete clinical work-up to exclude an underlying visceral adenocarcinoma. Primary cutaneous ectopic extramammary Paget's disease can be adequately treated with excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery and is associated with a good overall outcome and prognosis[3].

References: 1. Sarah H. Mehrtens, M.B., Ch.B., M.B. Sriramulu Tharakaram, and M.D. B.S., Extramammary Paget's Disease The New England Journal of Medicine, 2017. 376(17). 2. Hagiwara-Takita, A., et al., RANKL-Expressing Ectopic Extramammary Paget's Disease on the Lower Abdomen. Case Rep Dermatol, 2016. 8(2): p. 130-5. 3. Kim, S.J., et al., Surgical Treatment and Outcomes of Patients With Extramammary Paget Disease: A Cohort Study. Dermatol Surg, 2017. 43(5): p. 708-714.

Case 8: Onychocytic Matricoma

Caregivers: Jacqueline Brogan, MD, Jenny Yeh, MD, Morgan Fletcher, BS, Thomas Davis, MD; San Antonio, TX

History: A 30 year-old female presented with a 3-month history of a dark streak appearing on her right first toenail. The lesion was asymptomatic and she had no other nail pigmentation.

Physical Examination: Physical exam revealed a 3.0mm wide, somewhat streaky, longitudinal brown streak associated with thickening of the nail.

Histopathology: A 4.0mm punch biopsy of the nail matrix demonstrated a proliferation of the nail matrix epithelium with pigmented cells; MART-1 staining was negative.

Clinical Course: The patient did not return for follow up and was unable to be contacted to assure resolution of the lesion.

Diagnosis: Onychocytic matricoma

Points of Emphasis: Onychocytic matricoma (OCM) is a rare, benign, acanthoma of the nail matrix producing onychocytes. It is associated with acquired, localized thickening of the nail plate with longitudinal ridging and transverse hypercurvature, as well as longitudinal melanonychia (pachymelanonychia).1 On histopathology, the defining characteristics include endokeratinization in deeper layers of the tumor as well as prekeratogenous and keratogenous cells arranged in concentric nests.1 There may also be whorls of nail plate within the tumor stroma.2 This tumor can be classified according to pigmentation (pigmented or non-pigmented) and histological subtype (acanthotic, papillomatous or keratogenous with retarded maturation).1 Although pigmentation is often clinically present, melanocytes are typically not increased in number. 2 Our case can be classified as pigmented and acanthotic.

The differential diagnosis of OCM includes onychomatricoma (OM), onychocytic carcinoma (OCC), subungual keratoacanthoma, onychopapilloma and subungual melanoma. OM is a benign fibroepithelial matrical tumor that may also present as longitudinal pachyonychia with a thickened nail plate exhibiting ridging and transverse hypercurvature.3 The main histological factor that differentiates OM from OCM is the presence of prominent fibrous stroma with fibroblast proliferation in OM but not in OCM.3 As well, nail clippings can distinguish OM from OCM; while both exhibit thickened nail plates with cavities in a honeycomb pattern, OM nail clippings are characterized by large cavities, while OCM nail clippings are characterized by small cavities.3,4 OCC is a malignant epithelial matrical tumor that may also exhibit a similar clinical appearance as OCM.4,5 In contrast to OCM, OCC immunohistochemistry exhibits positive staining of p16 in the absence of p53 staining, indicative of an HPV-associated carcinoma.4 OCM can be distinguished from subungual keratoacanthoma and onychopapilloma through histopathologic findings.1,6

The most concerning differential of longitudinal melanonychia, often prompting nail biopsy, is subungual melanoma. Histopathology and immunochemistry distinguish subungual melanoma from OCM, as subungual melanoma classically displays cytologic atypia, pagetoid spread, confluent and multinucleated melanocytes, and lichenoid inflammatory reaction on histopathology; furthermore, immunoperoxidase stains (including HMB45, Melan-A, Sox-10 and MiTF) highlight the melanocytic proliferation in the matrix.7

As elucidated above, hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunohistochemistry of tissue samples is important in the diagnosis of OCM.1,3 Treatment recommendations for OCM have not been published, though excisional biopsy has been performed with no recurrence or persistence of the lesion.1,3

References: 1. Perrin C, Cannata GE, Bossard C, Grill JM, Ambrossetti D, Michiels JF. Onychocytic matricoma presenting as pachymelanonychia longitudinal: a new entity (report of five cases). Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(1):54-59. 2. Spaccarelli N1, Wanat KA, Miller CJ, Rubin AI. Hypopigmented onychocytic matricoma as a clinical mimic of onychomatricoma: clinical, intraoperative and histopathologic correlations. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(6):591-4. 3. Perrin C, Cannata GE, Langbein L, Ambrosetti D, Coutts M, Balaquer T, Garzon JM, Michiels JF. Acquired Localized Longitudinal Pachyonychia and Onychomatrical Tumors: A Comparative Study to Onychomatricomas (5 Cases)

Case 9: Acquired Subungual Fibrokeratoma in Pregnancy

Caregivers: Roya Nazarian, BA, Nikki Vyas, MD, Dana Stern, MD, Matthew Goldberg, MD, New York, NY

History: A 36-year-old female with no past medical history presented with a new onset nail lesion. She was in her 3rd trimester of pregnancy when she noted a new growth under the nail of her left first digit that was present for 3-4 weeks prior to presentation. The lesion occasionally bled, but she denied pain, pruritis, or other symptoms. She had no personal or family history of skin cancer.

Physical Examination: Physical exam was notable for a subungual, pink papule with a stalk that was 3-4 mm in length. All other exam findings were in normal limits.

Laboratory Data: Non-contributory.

Histopathology: An excisional biopsy was performed. Histopathologic exam of the lesion showed a fragment of nail plate and nail bed epithelium showing a flattened papule with overlying hyperkeratosis and fibrous stalk beneath the epidermis. The core of the papule showed dilated dermal vessels (oriented parallel along the vertical axis of the lesion) and increased, irregular collagen bundles, mimicking an acquired digital fibrokeratoma.

Diagnosis: The clinical and histopathological findings were most consistent with a benign subungual fibrokeratoma.

Clinical Course: The excisional site healed well without complication and the lesion did not recur.

Points of Emphasis: Acquired ungual fibrokeratoma is a rare and benign fibrous tissue tumor found in the periungual area. The term was first used in 1977 by Cahn et al, who believed the ungual fibrokeratoma was the same entity as the “garlic clove fibroma” first described in 1967.1 Because these tumors are exceedingly rare, they have not been clinically described well, yet a recent study of 20 patients found that 80% of ungual fibrokeratoms occur on toenails versus only 20% on the fingernails, and when found on the fingernails, only 5% are subungual.2 Lesions can present as rod-shaped, dome-shaped, flat, and branching. Histologically, acanthosis and thick collagen bundles oriented in the vertical axis with fibroblasts located in between collagen bundles can be seen.3 In 1985, Yasuki et al classified periungual fibrokeratoms into subtypes (Ip: within the proximal nail fold, Im: within the dermis beneath the nail matrix, Ib: within the nail bed, IIp: within the dermis of the dorsum of the distal phalanx, and IIl: within the lateral nail fold) based on the anatomical location.4 The case presented here would be classified as 1b because the lesion arises from the proximal nail folds in the subungual location with shallow, longitudinal, gutter-shaped depressions between two parallel ridges of the nail plate. While the exact etiology is unknown, both trauma and infectious etiology, mainly staphylococcal paronychia, have been proposed as predisposing factors.5,6 Treatment generally consists of complete surgical excision, as superficial excision has been noted to result in recurrence.7 We believe this is the first ever case describing an acquired periungual fibrokeratoma that developed during pregnancy, and we hope it will contribute to the existing literature by describing a novel presentation of a rare disease entity.

References: 1. Cahn RL. Acquired periungual fibrokeratoma. A rare benign tumor previously described as the garlic-clove fibroma. Archives of dermatology. 1977;113(11):1564-1568. 2. Hwang S, Kim M, Cho BK, Park HJ. Clinical characteristics of acquired ungual fibrokeratoma. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2017;83(3):337-343. 3. Goktay F, Altan ZM, Haras ZB, et al. Multibranched acquired periungual fibrokeratomas with confounding histopathologic findings resembling papillomavirus infection: a report of two cases. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2015;42(9):652-656. 4. Yasuki Y. Acquired periungual fibrokeratoma - A proposal for classification of periungual fibrous lesions. . The Journal of dermatology. 1985 12: 349-356. 5. Kint A, Baran R, De Keyser H. Acquired (digital) fibrokeratoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1985;12(5 Pt 1):816-821. 6. Sezer E, Bridges AG, Koseoglu D, Yuksek J. Acquired periungual fibrokeratoma developing after acute staphylococcal paronychia. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2009;19(6):636-637. 7. Shelley WB, Phillips E. Recurring accessory "fingernail": periungual fibrokeratoma. Cutis. 1985;35(5):451-454.

Case 10: Basal Cell Carcinomas Appearing During Immunotherapy for Reported Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma

Caregivers: Philip R. Cohen, Shumei Kato, Aaron M. Goodman, Sadakatsu Ikeda and Razelle Kurzrock; National City, CA; La Jolla, CA; and Tokyo, Japan

History: A 58-year-old man presented with newly appearing scaly red plaques on his left shoulder and left clavicle. His past medical history was significant for not only multiple primary cutaneous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), but also metastatic BCC to the brain, bone, liver and lungs 2 years earlier. His metastatic BCC had previously been unsuccessfully treated with vismodegib, stereotactic radiosurgery (for brain metastases), cisplatin and paclitaxel, sonidegib combined with buparlisib (a pan-class I PIK3 inhibitor), and vismodegib and paclitaxel. Hybrid capture-based next generation sequencing (HCNGS) of the metastatic BCC in the liver demonstrated a tumor mutational burden (TMB) of 103 mutations per megabase (/Mb; >19 mutation/Mb = high TMB) and 19 genomic alterations including amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2 and JAK2; he was started on the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab 240 mg intravenously every 2 weeks, with remarkable and rapid improvement of performance status and tumor shrinkage to near complete remission. The new skin lesions had appeared in the setting of near complete remission of his metastatic disease on continued nivolumab treatment.

Physical Examination: Erythematous plaques appeared on his left anterior shoulder and left chest.

Laboratory Data: HCNGS of the primary cutaneous skin tumors demonstrated a tumor mutational burden of 45 mutations/Mb and 8 genomic alterations. In contrast to the metastatic BCC in his liver, the primary skin cancers did not demonstrate amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2 or JAK2.

Histopathology: Superficial buds of basaloid tumor cells extend from the overlying epidermis into the dermis.

Clinical Course: The new skin BCCs were each treated with electrodessication and curettage. Follow up exam showed complete healing of the treated skin cancer sites without tumor recurrence. He continues to receive nivolumab every other week and his metastatic BCC continues to show over 95% regression on imaging.

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma: new cutaneous tumors during successful immunotherapy for metastatic disease.

Points of Emphasis: Genomically targeted therapies aimed at the Hedgehog pathway, such as vismodegib and sonidegib, are effective agents for treating patients with metastatic BCC. However, the patient’s metastatic BCC was resistant to these targeted therapies; indeed, his lack of response to treatments targeting a single genomic aberration is not surprising since his metastatic liver tumor had numerous alterations [1,2]. Checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab, may be effective immunotherapy agents for patients whose tumors have increased PD-L1 expression or multiple genomic aberrations (increased TMB) or both [3]. Of interest was the observation that in the setting of ‘late’ metastatic disease, the patient’s metastatic BCC was highly susceptible to anti-PD1 immunotherapy. Yet, he continued to develop new primary cutaneous BCCs--even though he was receiving nivolumab and his metastatic disease remained in near complete remission. The checkpoint inhibitor did not prevent his new skin cancers, perhaps since the ‘early’ primary disease had a lower TMB. In summary, immunotherapy may be best suited for ‘late’ disease in which the metastatic tumor has many genomic aberrations and an increased TMB in contrast to ‘early’ disease in which the primary cancer has fewer molecular alterations and a lower TMB [1].

References: 1. Cohen PR, Kato S, Goodman AM, Ikeda S, Kurzrock R. Appearance of new cutaneous superficial basal cell carcinomas during successful nivolumab treatment of refractory metastatic disease: implications for immunotherapy in early versus late disease. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(8). pii: E1663. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081663 . 2. Ikeda S, Goodman AM, Cohen PR, Jensen TJ, Ellison CK, Frampton G, Miller V, Patel SP, Kurzrock R. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma with amplification of PD-L1: exceptional response to anti-PD1 therapy. NPJ Genom Med 2016;1. pii: 16037. doi: 10.1038/npjgenmed.2016.37 . 3. Goodman AM, Kato S, Cohen PR, Boichard A, Frampton G, Miller V, Stephens, PJ, Daniels GA, Kurzrock R. Genomic landscape of advanced basal cell carcinoma: Implications for precision treatment with targeted and immune therapies. Oncoimmunology 2017;7(3):e1404217. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1404217

Case 11: Cutaneous Metastatic Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma and Hand-Foot Syndrome

Caregivers: Sarah Oberhelman, B.S., Emily Powell, M.D., Pamela Martin, M.D., Andrea Murina, M.D.; New Orleans, LA

History: A 58-year-old Hispanic man with stage 4 renal cell carcinoma (RCC) was referred to dermatology by hematology/oncology for evaluation of a palmar rash. The patient reported starting pazopanib 3 months prior following the diagnosis of metastatic RCC of the left femur and rib. He had stopped the medication for a month interval during which time he underwent left femur curettage with subsequent adjuvant radiation treatment to the femur. He had since restarted pazopanib. His palmar rash developed 1.5 months before presentation as painful red, hyperkeratotic papules and patches on his palms that enlarged and blistered. The lesions would eventually callous and fall off. During his initial evaluation, an unrelated red papule on the left cheek was noted during examination. The lesion had been present for the previous 2-3 months and was mildly tender.

Physical Examination: The patient was pleasant and in no acute distress. A single 2-3 mm mildly tender erythematous papule with surrounding telangiectasias was present on the left cheek. There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Numerous erythematous and scaly papules in various stages of development were present on the bilateral palms and elbows.

Histopathology: Punch biopsies of the left cheek and left elbow were performed. The left cheek biopsy showed a malignant spindle and epithelioid cell neoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for epithelial membrane antigen, pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, CD10, and PAX8 and negative for RCC antigen and PAX2, consistent with cutaneous, metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. The left elbow biopsy showed psoriasiform chronic dermatitis with eosinophilia.

Clinical Course: Following review of the histopathology from the left cheek biopsy, the patient was seen in clinic for suture removal and biopsy results were discussed with the patient. The patient was referred back to hematology/oncology where he subsequently received palliative radiation treatment. The palmar and elbow lesions were concerning for hand-foot syndrome, also known as palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia, given the patient’s history of a desquamating dermatitis following pazopanib treatment, physical exam findings, and consistent histopathology.1 The lesions improved with Clobetasol 0.05% cream applied twice daily.

Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastatic Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma and Hand-Foot Syndrome

Points of Emphasis: Cutaneous metastasis is a rare complication of any malignancy, most commonly seen in breast, lung, colon, and ovarian carcinomas as well as malignant melanoma.2 RCC metastasis only accounts for 4.6% of cutaneous metastases, most commonly occurring in patients with known clear cell carcinoma.3 Sarcomatoid differentiation is a form of high-grade transformation that can be seen in any histologic subtype of RCC and accounts for 5% of all primary RCC.4 Histologically, metastatic sarcomatoid RCC tumors appear similar to primary cutaneous tumors, so a high index of suspicion and immunohistochemical staining are essential for diagnosis.4 Vimentin and cytokeratin positivity are together suggestive of metastatic RCC rather than a primary tumor.5 While there is currently no good marker of sarcomatoid RCC available, PAX8 is considered the most sensitive marker, labeling 0-50% of metastatic lesions.4,5 Notably, PAX2 and RCC antigen are only expressed in up to 22% of primary sarcomatoid RCC, and metastatic sarcomatoid RCC is historically negative for PAX2.5

References: 1. Que Y, Liang Y, Zhao J, Ding Y, Peng R, Guan Y, Zhang X. Treatment-related adverse effects with pazopanib, sorafenib and sunitinib in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a pooled analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2141-2150. 2. Kishore M, Chauhan DS, Dogra S. Unusual presentation of renal cell carcinoma: A rare case report. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10(2):241-244. 3. Plaza JA, Perez-Montiel D, Mayerson J, Morrison C, Suster S. Metastases of soft tissue: a review of 118 cases over a 30-year period. Cancer. 2008;112:193-203. 4. Logunova V, Sokumbi O, Iczkowski KA. Metastatic sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma manifesting as a subcutaneous soft tissue mass. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2017;44:874-877. 5. Truong LD, Shen SS. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011; 135:92-108.

Case 12: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Caregivers: Christopher M. Lowther, MD, Troy Fiddler MD, PhD, Juanita Sapp, MD, Clay J. Cockerell, MD; Cody, WY, Billings, MT, Powell, WY, and Dallas, Texas

History: The 61-year-old white female presented with the four month history of a non-healing ulcerated mass approximately 3.5 cm in diameter on her right ankle.

Physical Examination: The patient had two small lesions, both on her right lower leg measuring 5 mm in diameter. Her ankle was painful and inflamed. She had diarrhea which started after two courses of doxycycline antibiotics, prior to referral. Lymphadenopathy was noted in the right inguinal area. The rest of her physical exam was unremarkable. All three lesions on her right leg underwent biopsy.

Laboratory Data: The only abnormal laboratory findings were hemoglobin was 10.9 g/dL with an MCV of 86.5 fl. A serum ferritin was 9 ng/ML (eight - 252 ng/ML). The consultant initially diagnosed metastatic squamous cell carcinoma versus pyoderma gangrenosum. The patient had no history of prior inflammatory bowel disease although there was a strong family history for colon cancer.

Histopathology: All three lesions were biopsied and demonstrated malignant basophilic neuroendocrine neoplasms thought to be either primary or metastatic. Immunoperoxidase stains were strongly positive for cytokeratin 20 and synaptophysin and negative for cytokeratin cocktail and TTF-1. A stain for CEA highlighted some of the background leukocytes. The diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma, likely Merkel cell carcinoma possibly metastatic, was rendered.

Clinical course: Computerized axial tomography revealed small non-calcified pulmonary nodules the largest measuring 6 mm in greatest diameter. There was a small 7 mm abnormality in the liver. There were large and suspicious appearing right-sided inguinal and lower abdominal wall lymph nodes in the right inguinal region and right iliac region. PET imaging was performed, from the skull to the toes. Focal hypermetabolic activity was noted at the left base of the tongue, with no hypermetabolic activity in the lungs. There was no evidence of mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy.

Liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, adrenal glands, kidney and vessels were unremarkable. The gastrointestinal track is unremarkable. Right inguinal lymphadenopathy with the largest lymph node measuring 19 x 21 mm with hypermetabolic activity maximum SUV value of 4.1 suspicious for metastasis.

Lymph nodes were seen along the right mid-thigh and lower leg medial with hyper metabolic activity. Diffuse soft tissue thickening around the distal tibia and fibula around the ankle with soft tissue defect and hypermetabolic activity maximum SUV value at 9.4 at the lateral ankle suspicious for known carcinoma. Biopsy was subsequently performed on the right inguinal lymph node and consistent with Merkel cell carcinoma.

Diagnosis: Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma, StagingT2, N3, MO equating to stage IIIB. The case was presented at St. Vincent healthcare tumor board and recommendation was to proceed with systemic therapy due to extent of disease. StagingT2,N3, MO equating to stage IIIB.

The newly approved PD-LI for Merkel cell carcinoma, Avelumab, was started. She was not considered a surgical candidate by the tumor board. Following the start of cycle four of chemotherapy, the right ankle had almost completely resolved. She tolerated the treatment without complications. Follow-up axial tomography of chest abdomen and pelvis and right lower leg was ordered.

Points of emphasis: The primary lesion of Merkel cell carcinoma is often distinguished by the absence of distinctive clinical characteristics and is rarely suspected at the time of biopsy. It often presents as a rapidly growing reddish blue dermal papule or nodule.5

Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin was first described by Toker in 1972 and initially thought by him to represent a sweat gland carcinoma. Further study revealed the presence of dense corps granules of the tactile Merkel cells.1,2,3,4 Upon presentation 66% of patients have local disease, 27% nodal involvement and 7% distal metastasis.2,4 The majority of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma are 70 years or older with an increased incidence in renal transplant patients, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and HIV.1 Polyomavirus is associated with 80% of tumors.4 The primary lesion of Merkel cell carcinoma is often distinguished by the absence of distinctive clinical characteristics and is rarely suspected at the time of biopsy. It often presents as a rapidly growing reddish blue dermal papule or nodule.5

Avelumab, the human anti-PD-L1 antibody, is the first immunotherapy approved for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, for adult and pediatric patients 12 years and older with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare and aggressive skin cancer with fewer than half the patients surviving more than one year and fewer than 20% surviving beyond five years.6 Immunochemistry is often definitive. Merkel cells are almost impossible to see on light microscopy in normal skin and without immunohistochemical stains are nearly impossible to detect.5 CK 20 is the predominant tool used by pathologists and stained approximately 80 to 90% of all Merkel cell carcinomas and a distinctive para nuclear-dot like pattern.5,7

Approximately 53% of Merkel cell carcinomas occur in the head and neck and 35% occur on the extremities. In the Javelin Merkel Cell Carcinoma 200, a phase 2 clinical trial, at the median follow-up of 16.4 months of which 88 patients had been enrolled and treated with Avelumab, the overall response rate was 33% (29 patients), partial response rate was 22% and complete response was 11%. 86% of tumor responses lasted at least six months (25 patients) and 45% lasted at least 12 months (13 patients).8

References: 1.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch of Dermatol 1972; 105:107 – 110 2. Han S, North J, Canavan T, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Amer. 2012; 26:1351 – 1374 3. Goessling, W, Mckee P, Mayer R. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002; 20:588 – 598. 4. Oram C , Bartus C S, Purcell S. Merkel cell carcinoma: A review. Cutis. 2016 Volume 97, 4 to 90 – 295 5. Wang T, Byrne, P, Et al, Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011 Mar:30 (1) 48-56 . 6. Lemos B, Storer B, Lyer J, et al. Pathologic nodal evaluation approves prognostic accuracy and Merkel cell carcinoma; J Amer Acad Derm. 2010; 63(5): 751 – 761. 7. Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, et al. immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Dermatopathol. 2006; 28:99 – 104. (Pub Med) 8. Pearson, J , Meyers, A Skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma, Medscape updated March 27, 2017

Case 13: Ewing’s Sarcoma in an Adult- A Rare Entity

Caregivers: Leah Persad, DO, Amit Patel, MD, Jerad Gardner, MD Clay Cockerell, MD; Dallas, TX, Nederland, TX, Little Rock, AR

History: A 75-year-old woman presented with a 1 cm erythematous nodule on the right anterior shoulder. The lesion had been present for an undetermined period of time.

Physical Exam: Involving the right anterior shoulder was a 1 cm, round pink to erythematous smooth firm nodule.

Histopathology: A biopsy of the lesion revealed dermal sheets of small round blue cells with uniform round nuclei, scant cytoplasm, relatively minimal pleomorphism but with many mitotic figures. The tumor was diffusely and strongly positive for CD99, showed rare positivity for synaptophysin and was negative for EMA, Pan-CK, CD45, SOX-10, SMA, CK20, TTF-1, CD43, MUM-1, TdT, CD34, and p40. Cytogenetic and molecular testing of the tumor was positive for rearrangement of the EWSR1 (22q12) locus by FISH. An EWSR1/FLI1 fusion transcript was detected by RT-DNA amplification respectively.

Clinical Course: The patient was referred to MD Anderson Cancer Center for further workup to rule out additional involvement.

Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Ewing Sarcoma in an Adult

Points of Emphasis: Ewing sarcoma (ES) is a small round blue cell tumor that is closely related to the primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) family. Ewing sarcoma is typically a neoplasm that occurs in bone or soft tissue of children and young adults. Rarely, it can present as a primary cutaneous neoplasm in adults. In this setting, the mean age is 22 years (range from 22 months to 77 years) with a nearly 2:1 female predominance. The median size of tumors reported was 2-3 cm most commonly on the extremities, followed by the head and trunk. Radiologic and clinical correlation is essential to confirm that the lesion is small and confined to the skin rather than a metastasis or direct extension from deep soft tissue or bone.

Histopathology typically reveals a nodular or sheet-like proliferation of undifferentiated small round blue cells. In this setting, there is a wide range of differential diagnoses when occurring in an adult including Merkel cell carcinoma, metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung, lymphoma and small cell melanoma. Ancillary studies can help further differentiate these entities. ES/PNET almost always characteristically show diffuse positivity for CD99 in a membranous pattern. Rarely, Merkel cell carcinomas and lymphoblastic lymphoma can express CD99 so that other stains may be required to distinguish these, however. ES/PNET may infrequently display focal positivity for pancytokeratin, S100, and neuroendocrine markers. Based on the varied immunohistochemical pattern of staining, there can be some diagnostic confusion between these entities, in which morphological and clinical correlation can aid in the diagnosis.

The characteristic chromosomal translocation in ES/PNET t(11;22)(q24; q12) resulting in the EWSR1-FLI1 fusion gene can greatly aid in the diagnosis. However, approximately 10% of ES/PNET have variant translocations. Rarely, the EWSR1 gene can be identified in other morphologically distinct entities as it has been described as a “promiscuous” gene.

Dual color break-apart EWS FISH probes can detect EWSR1 rearrangements regardless of the translocation variants. In this break-apart probe strategy, fluorosceinated probes normally flank the EWSR1 gene. In the nucleus, abnormal (separate) red and green fluorochromes signify disruption of one copy of the EWSR1 gene. In contrast, the normal allele is intact as evidenced by fused red and green signals indicating that the two probes are juxtaposed as a consequence of binding the same chromosomal locus.

Based on the relatively limited data in the literature on primary cutaneous Ewing sarcoma, it appears to have a much better prognosis than its skeletal or deep soft tissue counterpart. It has been established that the 10-year probability of survival was 91% with rare chance of metastatic disease. In light of the excellent prognosis of this tumor when confined to the skin, some authors have suggested that surgical excision should be the primary mode of treatment with adjuvant therapy such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy playing a lesser role.

References: 1. Delaplace M, Lhommet C, de Pinieux G, Vergier B, de Muret A, Machet L. Primary cutaneous Ewing sarcoma: a systematic review focused on treatment and outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Apr;166(4):721-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10743.x. Epub 2012 Mar 5. 2. Boland JM, Folpe AL. Cutaneous neoplasms showing EWSR1 rearrangement. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013 Mar;20(2):75-85. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31828625bf. 3. Machado I, Traves V, Cruz J, Llombart B, Navarro S, Llombart-Bosch A. Superficial small round-cell tumors with special reference to the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors and the spectrum of differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2013 Feb;30(1):85-94. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2012.01.007. 4. Shingde MV, Buckland M, Busam KJ, McCarthy SW, Wilmott J, Thompson JF, Scolyer RA. Primary cutaneous Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour: a clinicopathological analysis of seven cases highlighting diagnostic pitfalls and the role of FISH testing in diagnosis. J Clin Pathol. 2009 Oct;62(10):915-9 5. Collier AB 3rd, Simpson L, Monteleone P. Cutaneous Ewing sarcoma: report of 2 cases and literature review of presentation, treatment, and outcome of 76 other reported cases. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011 Dec;33(8):631-4

Case 14: Acquired Unilateral Nevoid Telangiectasia

Caregivers: Julia Accetta, MD, Cather McKay MD, and Howard Patrick Ragland MD; New Orleans, LA

History: A 60-year-old female with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and Sjogren's syndrome well-controlled on tocilizumab, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine, presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic red lesion on the plantar surface of her right foot. Her regular pedicurist brought the lesion to her attention at their last visit four weeks ago and since then, she has not noticed any changes. She denies associated pain or itching. No similar lesions elsewhere.

Physical Examination: Patient is well-appearing. On the right plantar foot there is a non-tender partially blanchable retiform deep-red patch extending from the great toe to the instep. She has no other skin lesions on total body skin exam. She has diffuse joint deformities including deviations of MCPs and metatarsals.

Laboratory Data: Recent complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein were all within normal limits.

Histopathology: Punch biopsy of right plantar foot showed a proliferation of dilated blood vessels in the epidermis consistent with telangiectasia. There was no evidence of thromboembolism, malignancy, or vasculitis.

Clinical Course: Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was monitored and no change in the current lesion and no new lesions have appeared.

Diagnosis: Acquired unilateral nevoid telangiectasia

Points of Emphasis: Unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT) is a vascular dermatosis characterized by superficial telangiectasias in a unilateral and segmental distribution. UNT can be either congenital or acquired. The congenital form is due to a rare, autosomal dominant somatic mutation that occurs most commonly in males shortly after the neonatal period. The acquired form is thought to be secondary from elevated estrogen. Although rarely reported in the literature, UNT may be common but under diagnosed due to its asymptomatic presentation.

Clinically, UNT appears as multiple patches of superficial, blanchable telangiectasias that appear in a unilateral, linear distribution. The lesions may be Blaschkoid or follow a dermatomal distribution, favoring the third and fourth cervical dermatomes. Sometimes, an anemic halo, or pale ring surrounding the telangiectasia may be noted. Differential includes hemangioma, primary telangiectases i.e. linear atrophoderma of Moulin, angioma serpiginosum and secondary telangiectases i.e. erythema ab Igne or an adverse effect from topical steroids (1).

On histology, there are multiple, dilated, thin-walled vessels in the superficial papillary dermis, without cell proliferation or angiogenesis and minimal inflammation (2). Laser-Doppler flowmetry can identify alterations in local blood flow such as hyperperfusion.